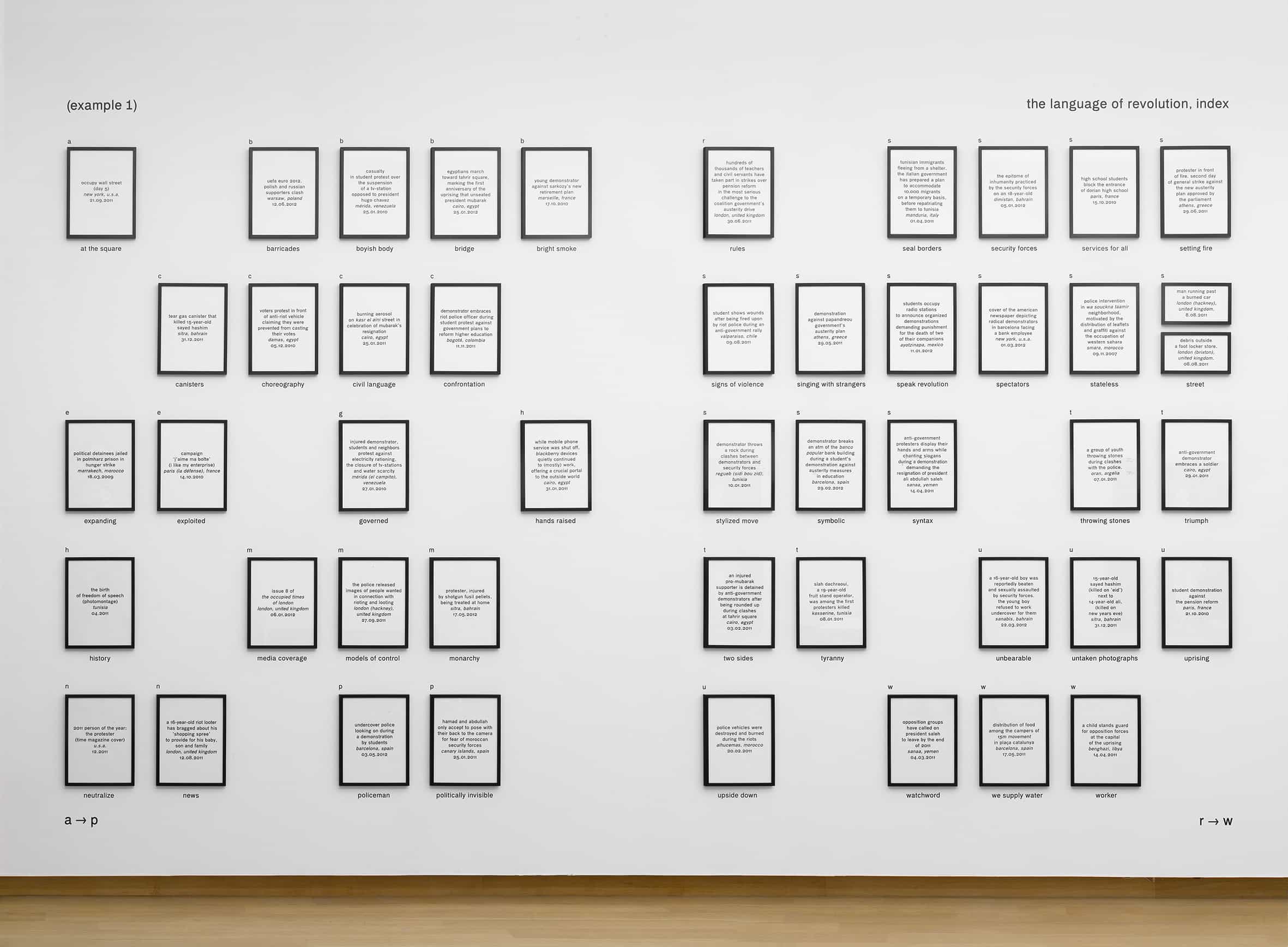

Yes With Us, Never About Us:

Art/Workers, Solidarity and Privilege(1)

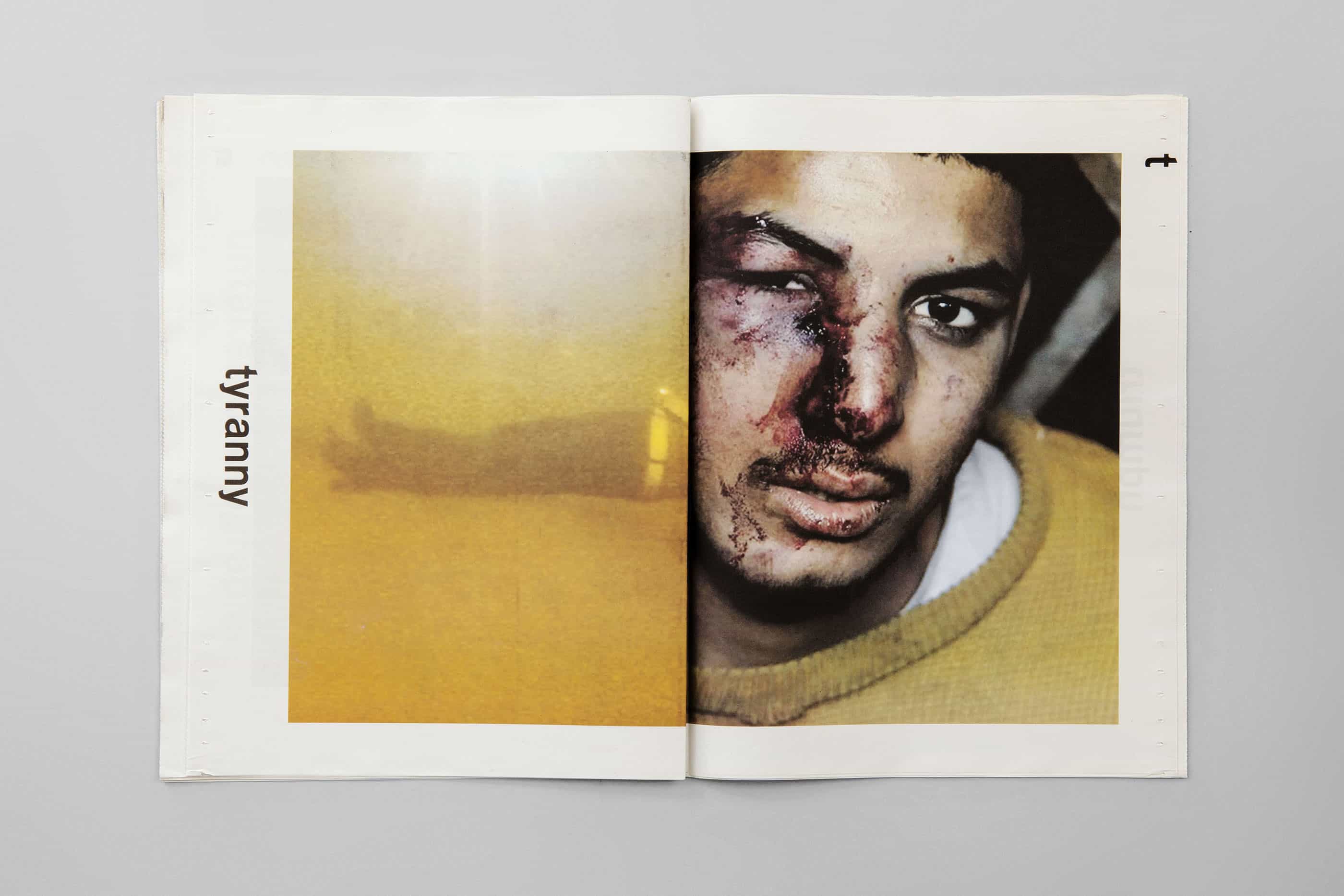

The history of artists engagement in workers struggles is as long as the distrust of intelligentsia by the revolutionary working class. After the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, more than 160 intellectuals were expelled with their families on so-called Philosophers Ships from Petrograd (today Saint Petersburg) to Stettin in Germany (today Szczecin, Poland). Later, in 1922, more intellectuals were to be transported by train to Riga or by ship from Odessa to Istanbul. Contemporary examples of artist persecution can be found in the Republic of Cuba or China, where artists and intellectuals are subjected to arbitrary arrest and detention, accused of promoting dissident behavior. In 2019, The National Assembly of People’s Power in Cuba approved a decree in the new constitution (Decreto 349) that enforces state control over art events and obliges all artists to adhere to official cultural institutions.(2) A new authority has been introduced known as the cultural inspector’, with powers to stop any artistic manifestation considered to not be conforming with the ideals of the revolution.

Paradoxically, under the dictatorship of the proletariat, art and culture seem to be taken seriously by the state. As potential catalysts of social change, the production of culture in such political contexts must be either channeled by state institutions or repressed otherwise. The seemingly larger degree of individual freedom in our modern democracies contrast with the often-questioned agency of politically engaged art practices and academic critical knowledge. Can socially engaged art bring any real social and political change to society or does it only serve governments as a cosmetic excuse to sooth critical voices and preserve the status quo?

Written in an Italian fascist prison from 1929 to 1935, Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks sketch the first Marxist theory to analyze culture as a fundamental part of the superstructure of society. Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony describes how civil society creates, through a variety of cultural forms, a common sense. or consensus that is necessary for any kind of social and economic activity to take place. Analyzing Gramsci in the scope of post-truth rhetoric, the presidents Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro or Andrzej Duda don’t hesitate to exacerbate social antagonism with fake news. in order to gain popularity by opposing the local working class to migrant workers, heteronormative families to LGBTQI+ communities, patriarchy to feminist movements, intellectuals to other practical professions or white hegemony to racialized populations. It is plausible to suggest that today’s politics are increasingly influenced by the technological developments that incessantly reshape the way in which culture and ideology are created and shared. To use Gramscian terminology, capitalist societies produce a common sense. to benefit the ruling class. To subvert the status quo, it is essential to create a culture from below. How can intellectuals and artists contribute to the formation of counterculture? Are artists and intellectuals a part of the dominant class or can they provoke social change? Gramsci defined two kinds of intellectuals: the traditional intelligentsia which sees itself as a class apart from society and theorganic intellectuals. which articulate through culture the invisible experiences of the oppressed.

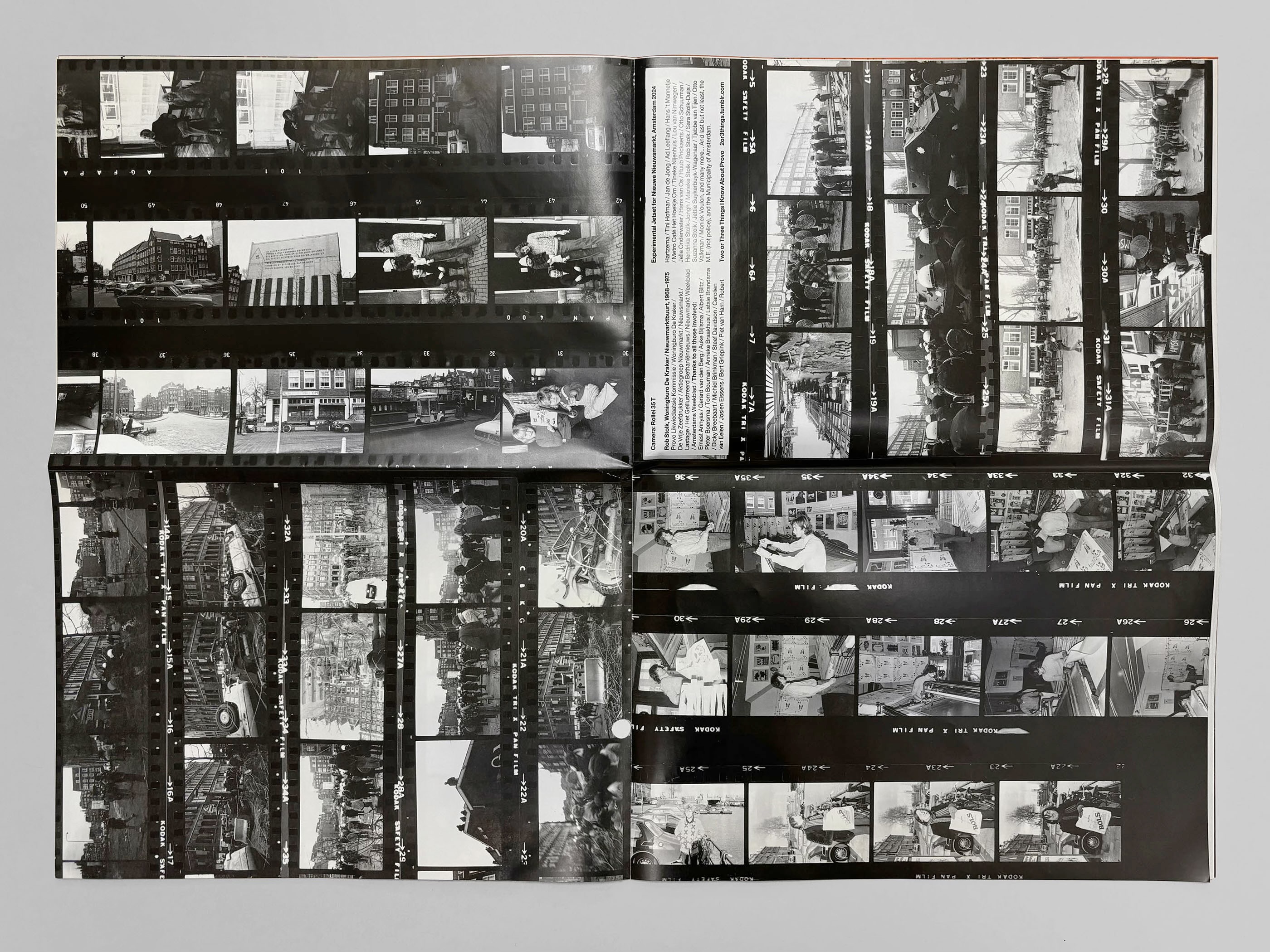

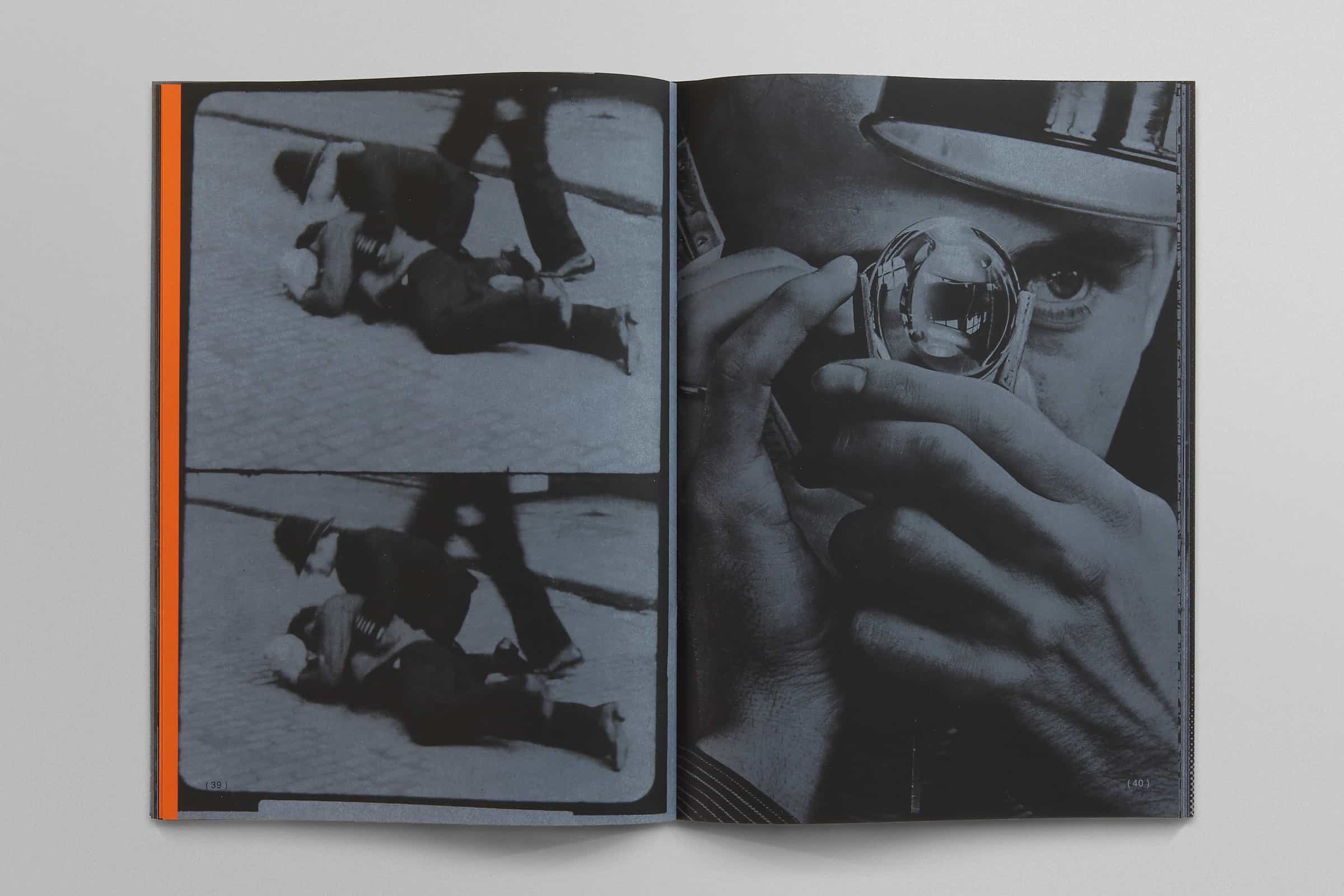

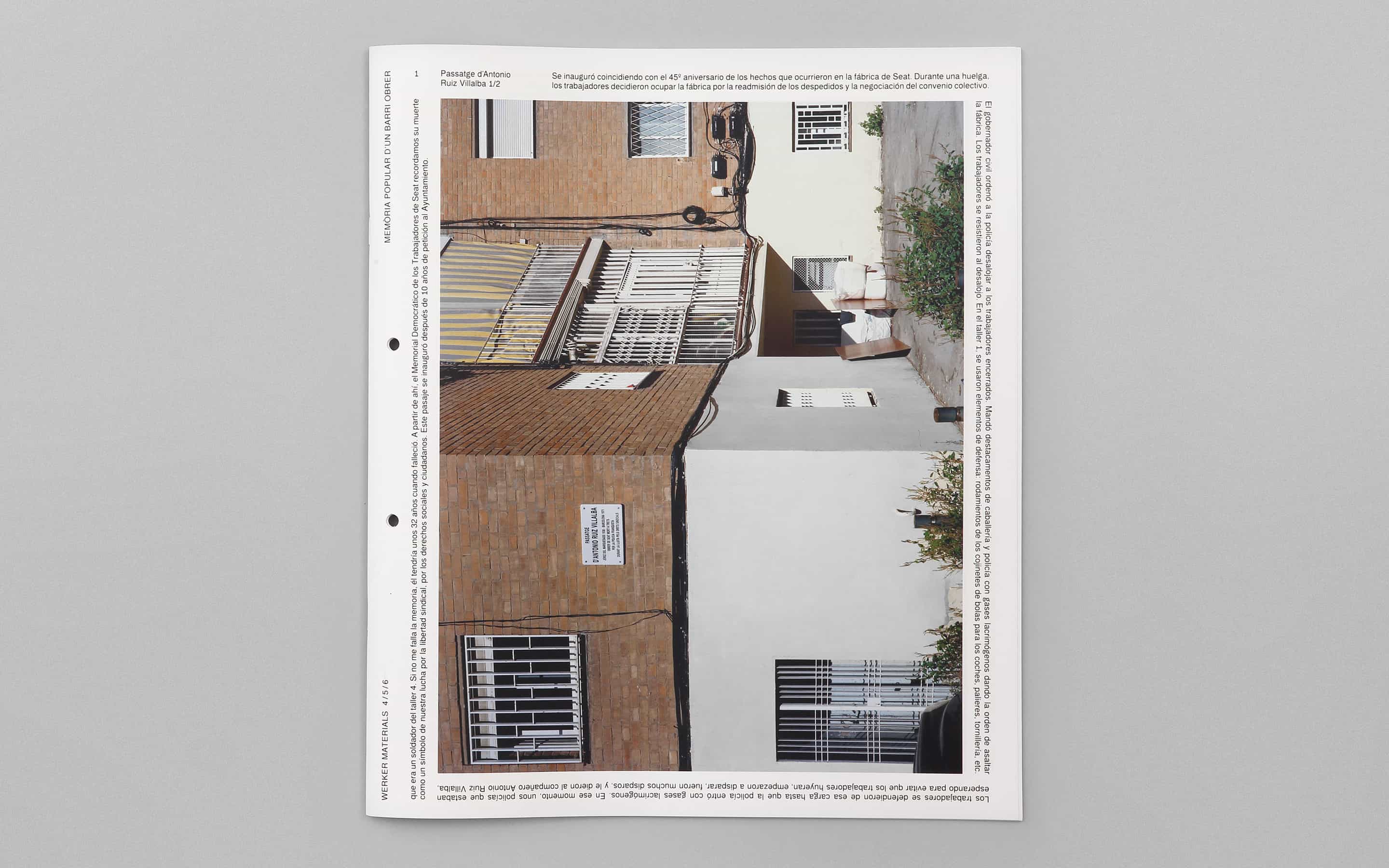

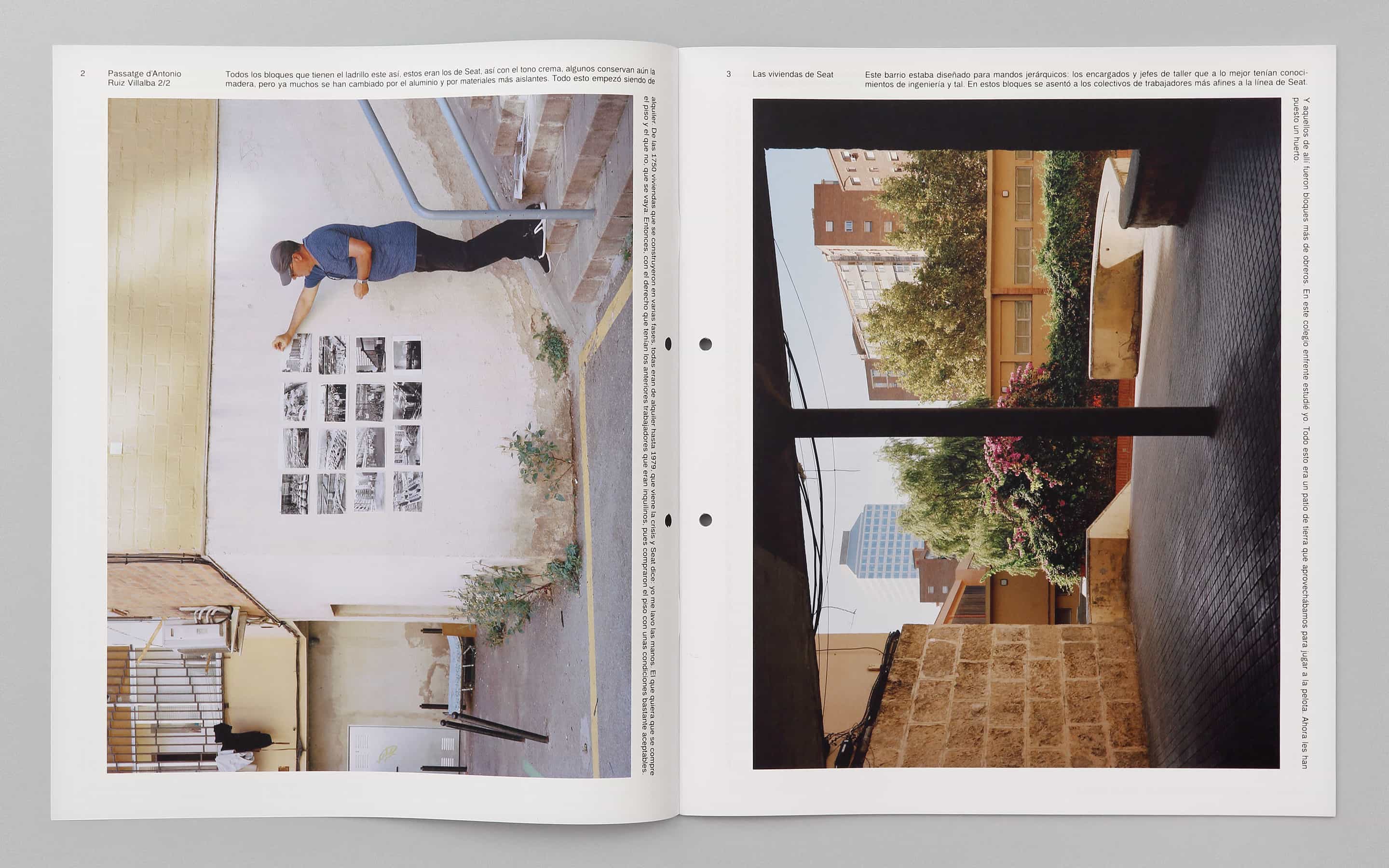

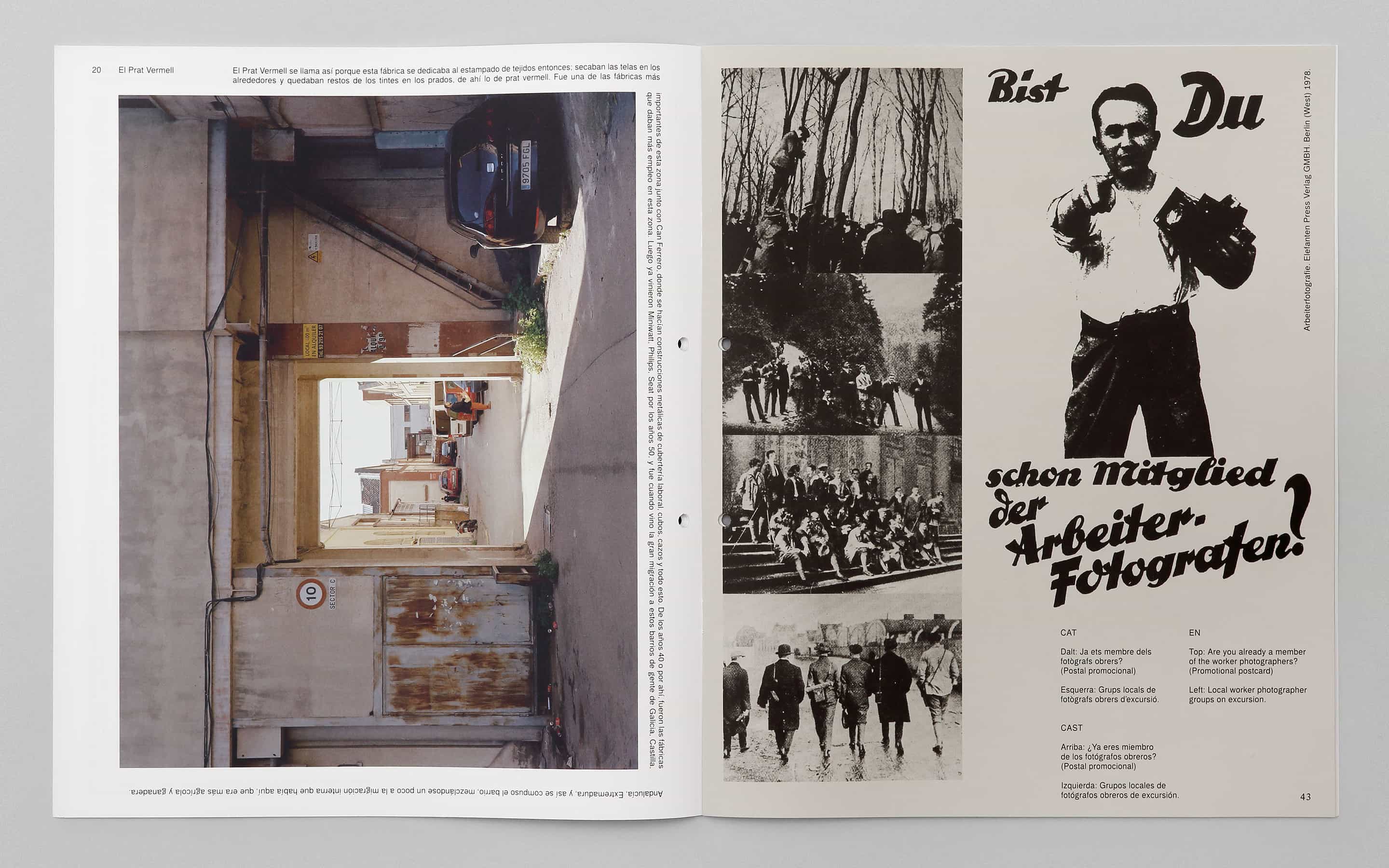

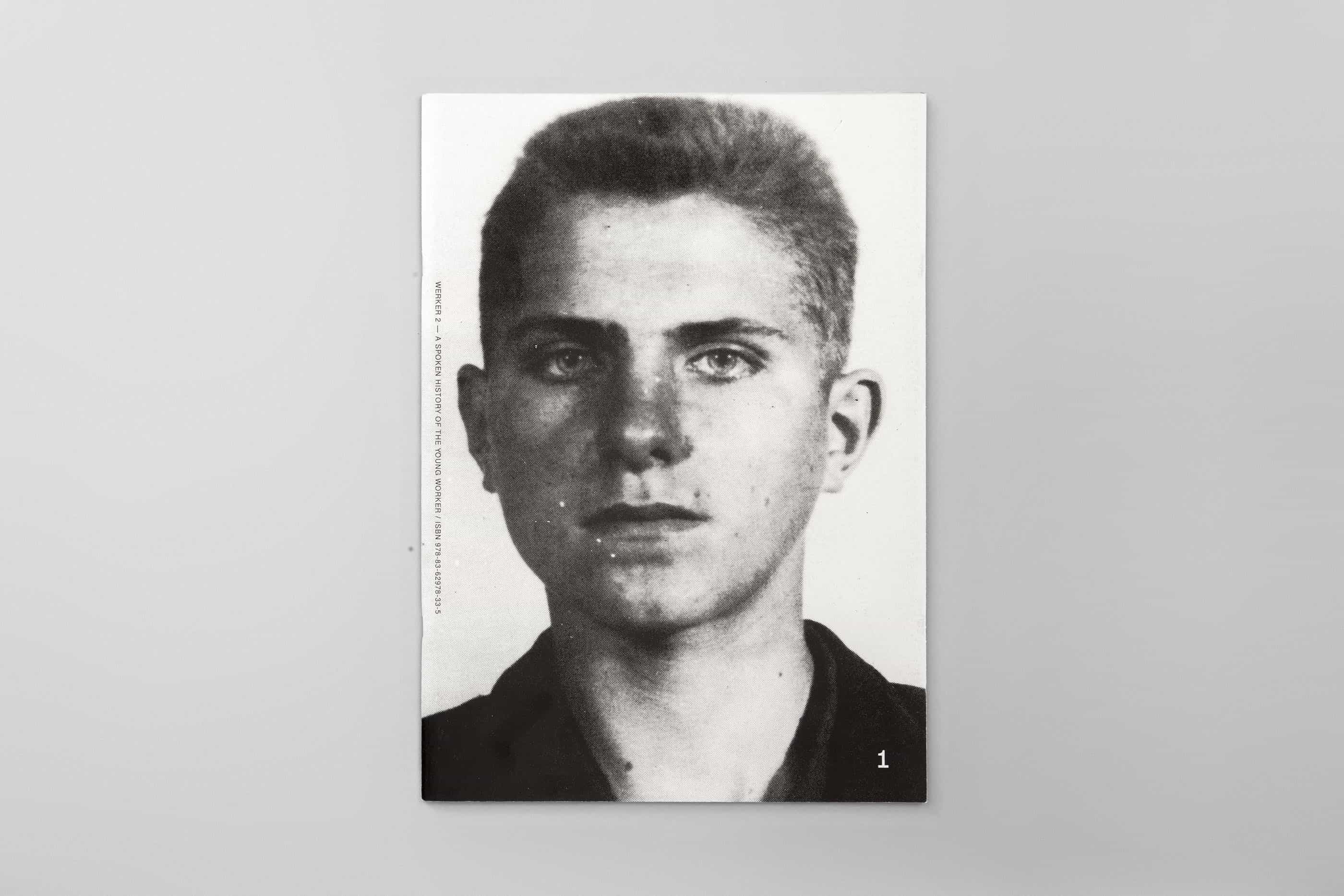

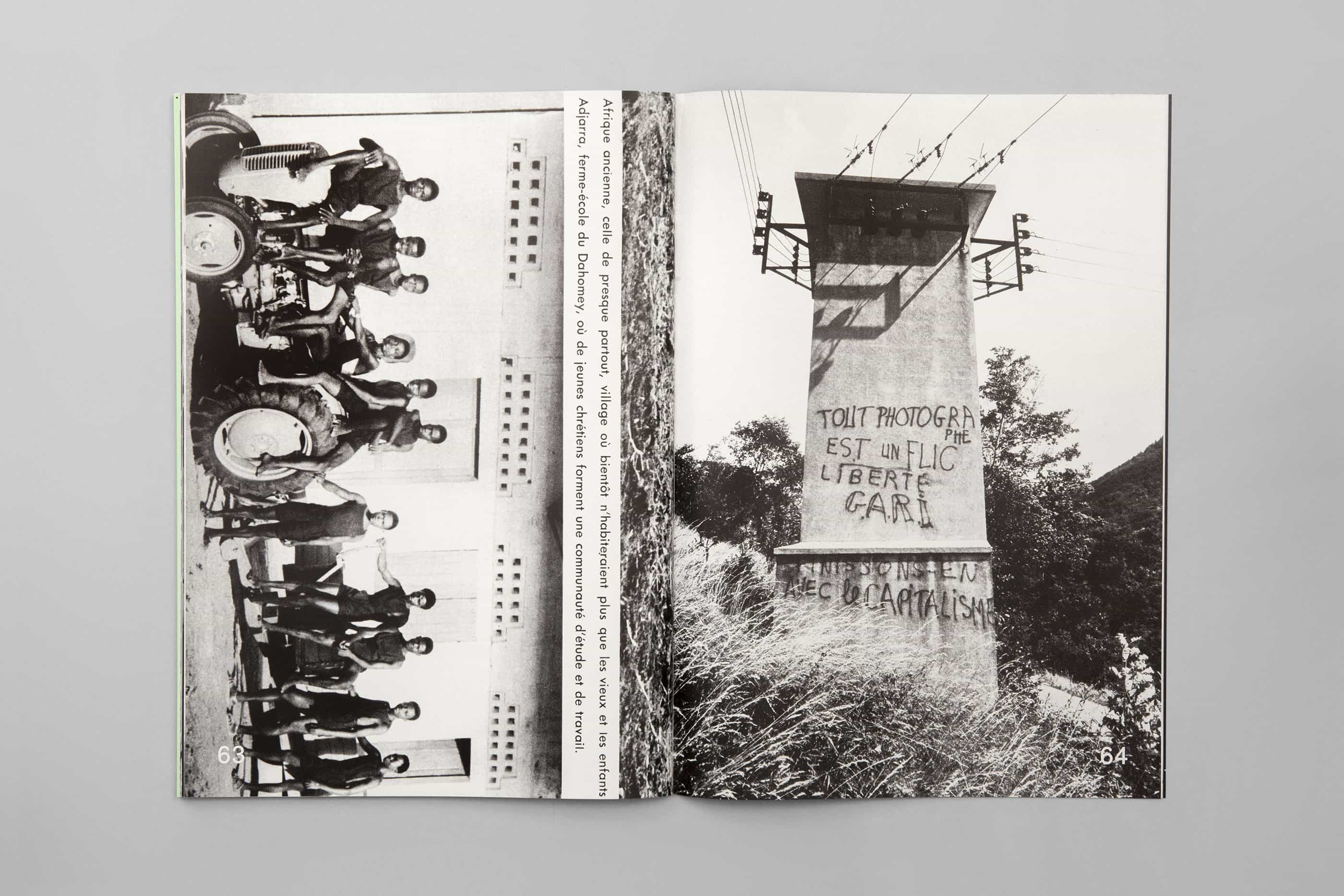

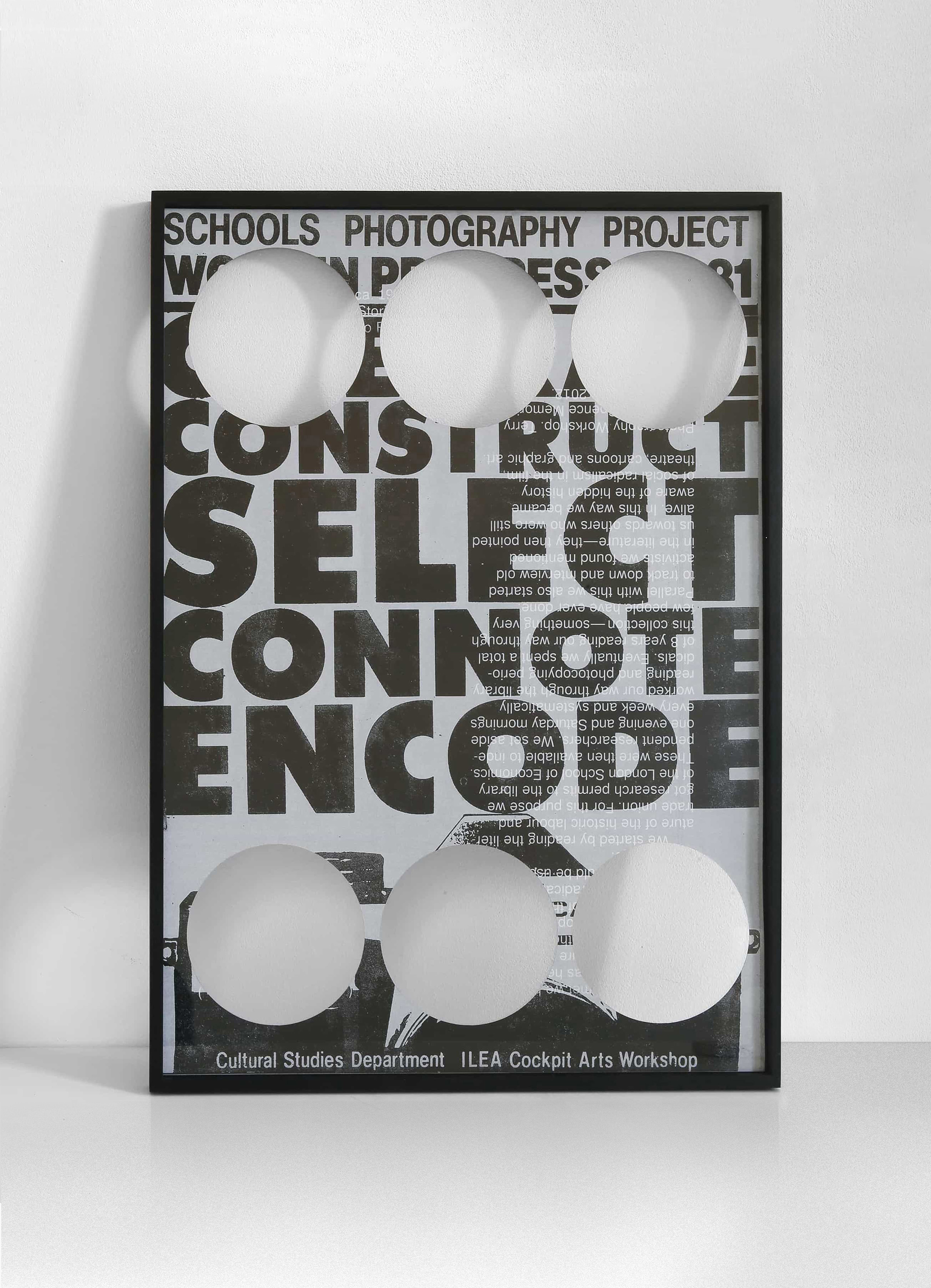

From our perspective, an example of what Gramsci considered an organic intellectual. would be political activist and communist Willi Münzenberg who founded der Vereinigung der Arbeiter-Fotografen (The Association of Worker Photographers) in 1926 which was a group of associations in Germany aimed at making photography accessible to workers and the unemployed. Münzenberg’s network of politicized photo clubs were pioneering in challenging the hierarchy inherent to traditional forms of art and media production, notably the separation between authors. and subjects’. The Worker Photographers often signed their images under group names, valorizing the collective effort of representing daily struggle over authorship. This experiment of direct participation of workers in the production of representations of daily life lasted until 1933, when the German Communist Party became illegalized by Hitler. Similar collectivist experiences to Münzenberg’s photo clubs took place in the first years of the Bolshevik Revolution in the Soviet Union but rapidly lost its communal nature under Stalin’s totalitarian dictatorship. In 1940, Münzenberg was found dead in Bois de Caugnet, France. The circumstances of his death remain unclear, but evidence seems to indicate that he was killed by a Soviet agent under the orders of Stalin. From 1938 onwards, Münzenberg stood publicly against Stalin’s repressive politics, namely the Great Purge that killed between 600,000 and one million people comprising of rich land owners, members of the intelligentsia and the Soviet Communist Party that Stalin considered potential opponents to his mandate.

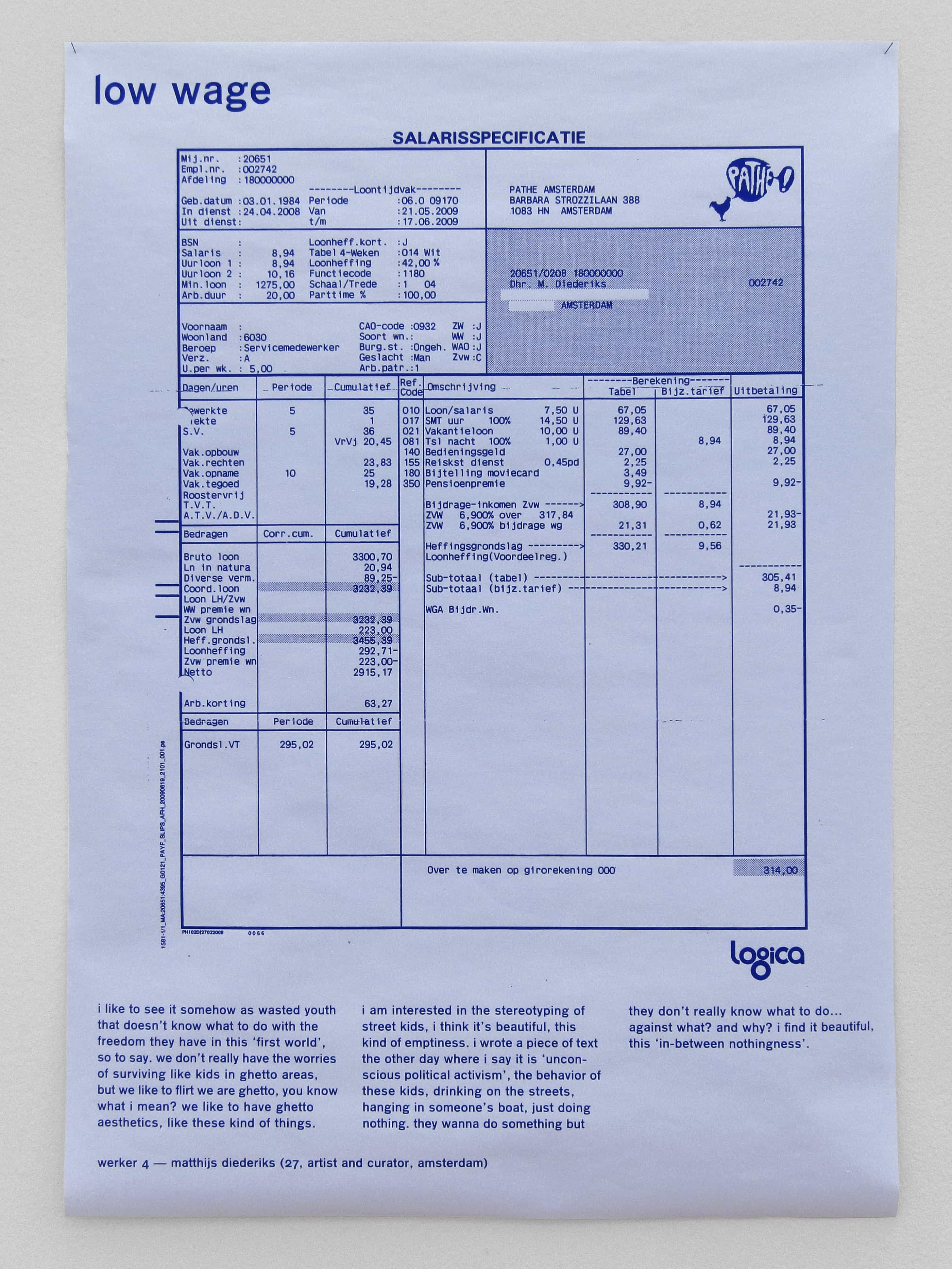

In the late 1960s, the research by French Marxist philosopher, Louis Althusser, shed light on how ideology is transferred from the state to the population and became useful to identify less obvious forms of control of artistic expression and critical thinking that take place in our modern democracies. Bureaucratic procedures filter the access to public funds for arts and culture. Commercial interests and sponsors influence the agenda of museums, festivals and academies. Private investors set the market value of artworks. In parallel, meritocracy and cultural elitism regulate which artists and intellectual voices are validated. Differences in class, gender, race, sexuality and religion keep on determining which voices are heard, which artists can financially sustain themselves with their artistic practice and which forms of knowledge are recognized with institutional visibility.

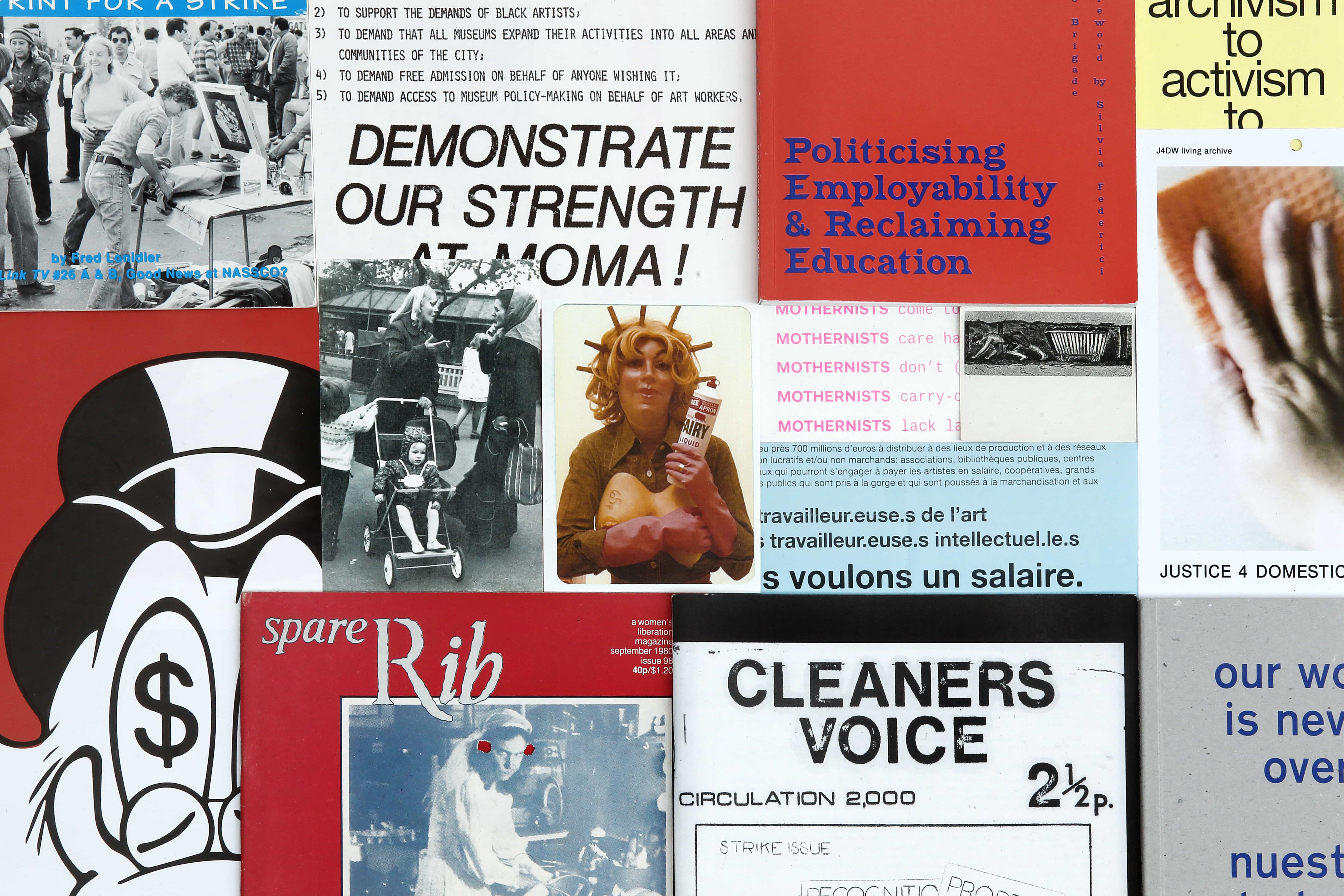

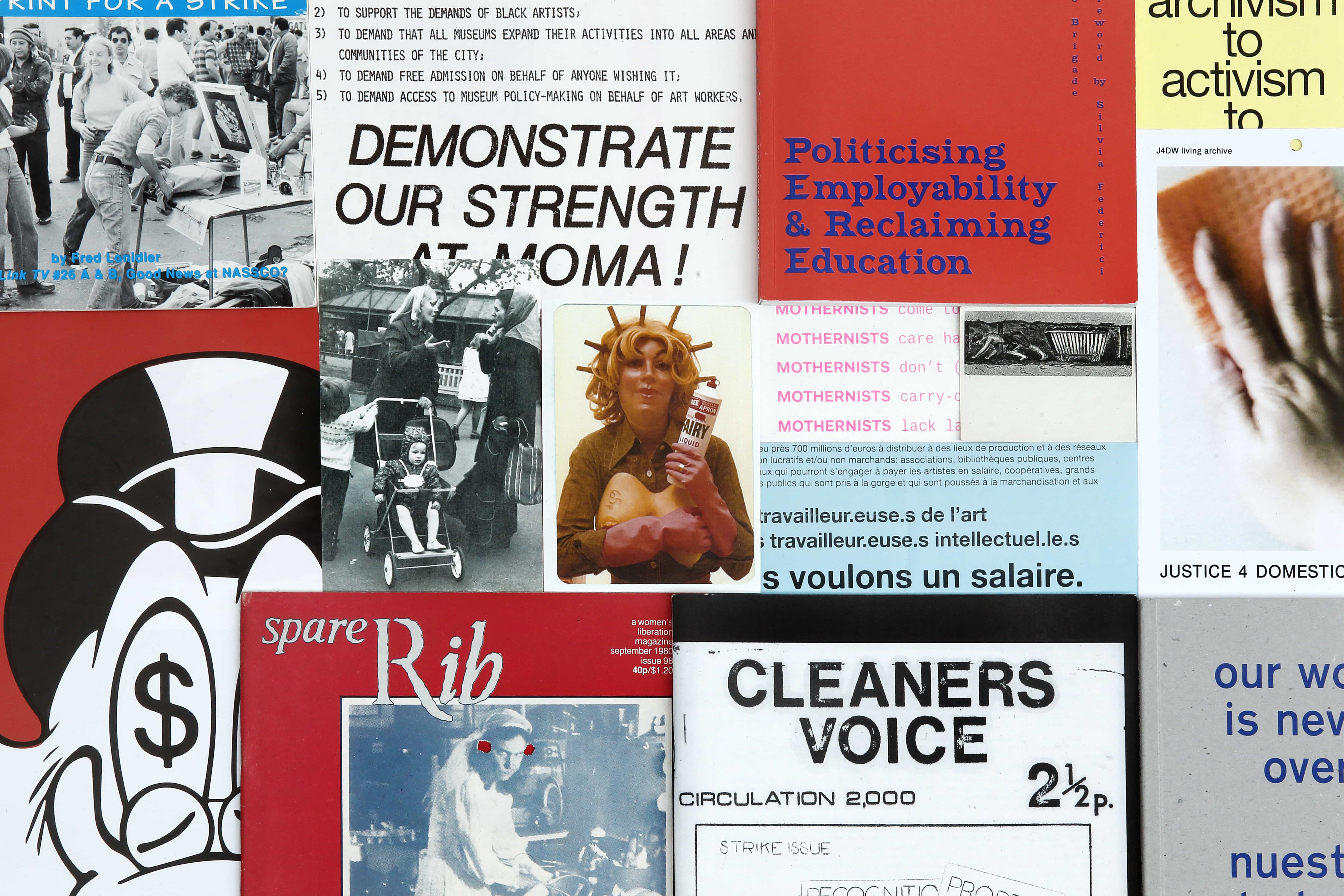

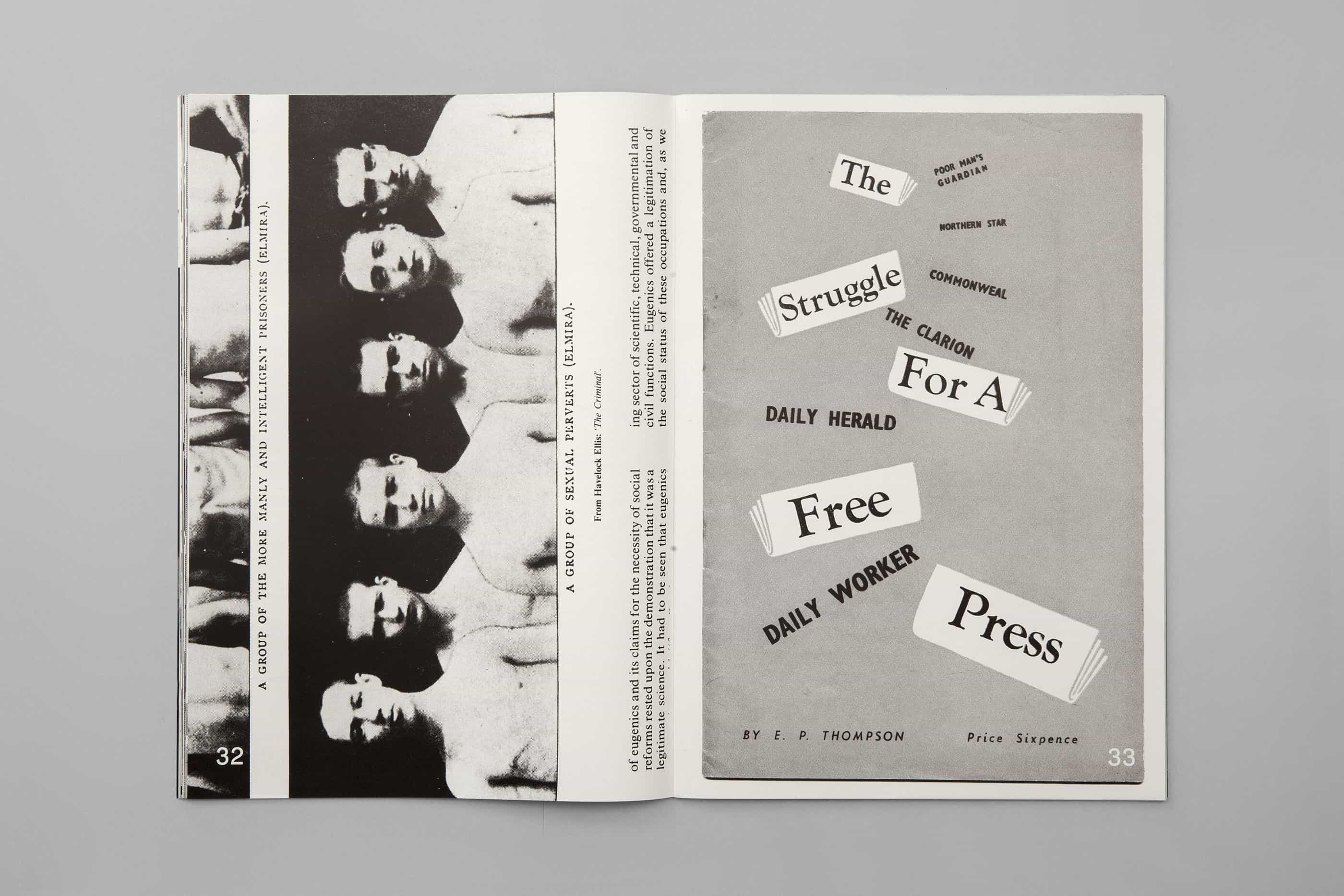

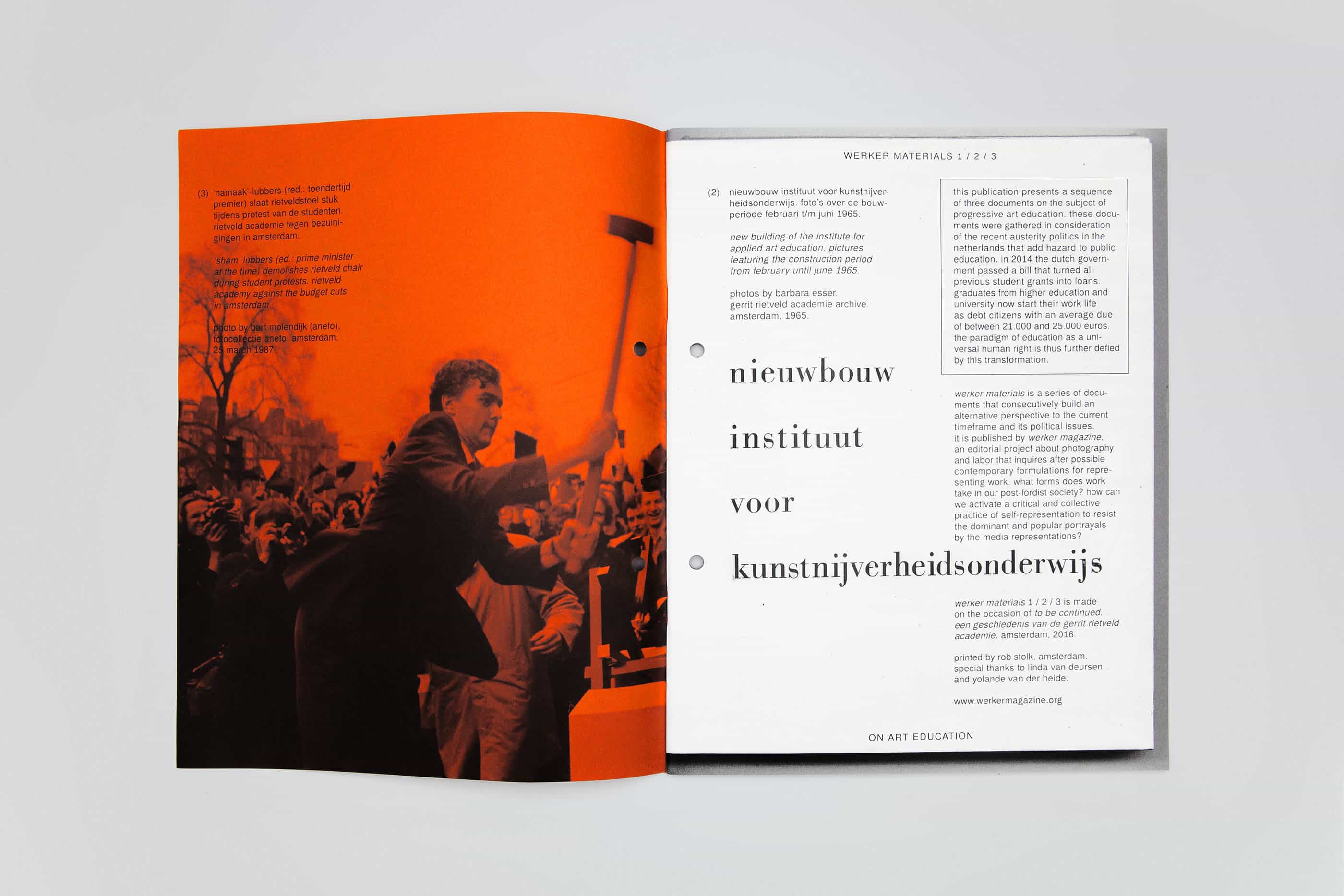

In 1969, the Art Workers. Coalition in New York wrote a list of 13 demands addressed to city museums to implement economic and political changes and reassess the museum’s relationship to artists and society. The list included demands such as the access to welfare for artists, rent control for artist housing and guidelines for museums to properly remunerate their work. There were also demands for measures to increment the presence of non-white and non-male artists and audiences in the museums. More than 50 years later, these demands are still unfulfilled. Self-organized groups in different geographies such as the Precarious Workers Brigade,(3) Guerrilla Girls(4), or The Black Archives(5) are currently campaigning against the exploitation of art workers and the unrecognition and erasure of non-male and non-white narratives. Beyond the Gramscian opposition between traditional and organic intellectuals, whose differentiation lies in which ideology and social class they represent in their oeuvre, the Art Workers. Coalition approached the artist’s relationship to society through the perspective of labor, gender and race liberation movements. The artist, as a worker, should equivalate their rights to other professional fields and be protected by a society that is articulated around the dictates of a productive economy. The artist as a woman and/or a mother should be cared for by a society that takes reproductive labor for granted and assigns care work to only women. The non-white artist should be cared for and compensated by a society whose wealth is based on hundreds of years of slavery and the exploitation of colonized lands and cultures. In our opinion, to exclude the artist from the possibility of also being a worker. might have the effect of both mystifying the figure of the artist by assuming (traditional) concepts of authorship and alienating their position in society, thus compromising the political agency of the arts at large.

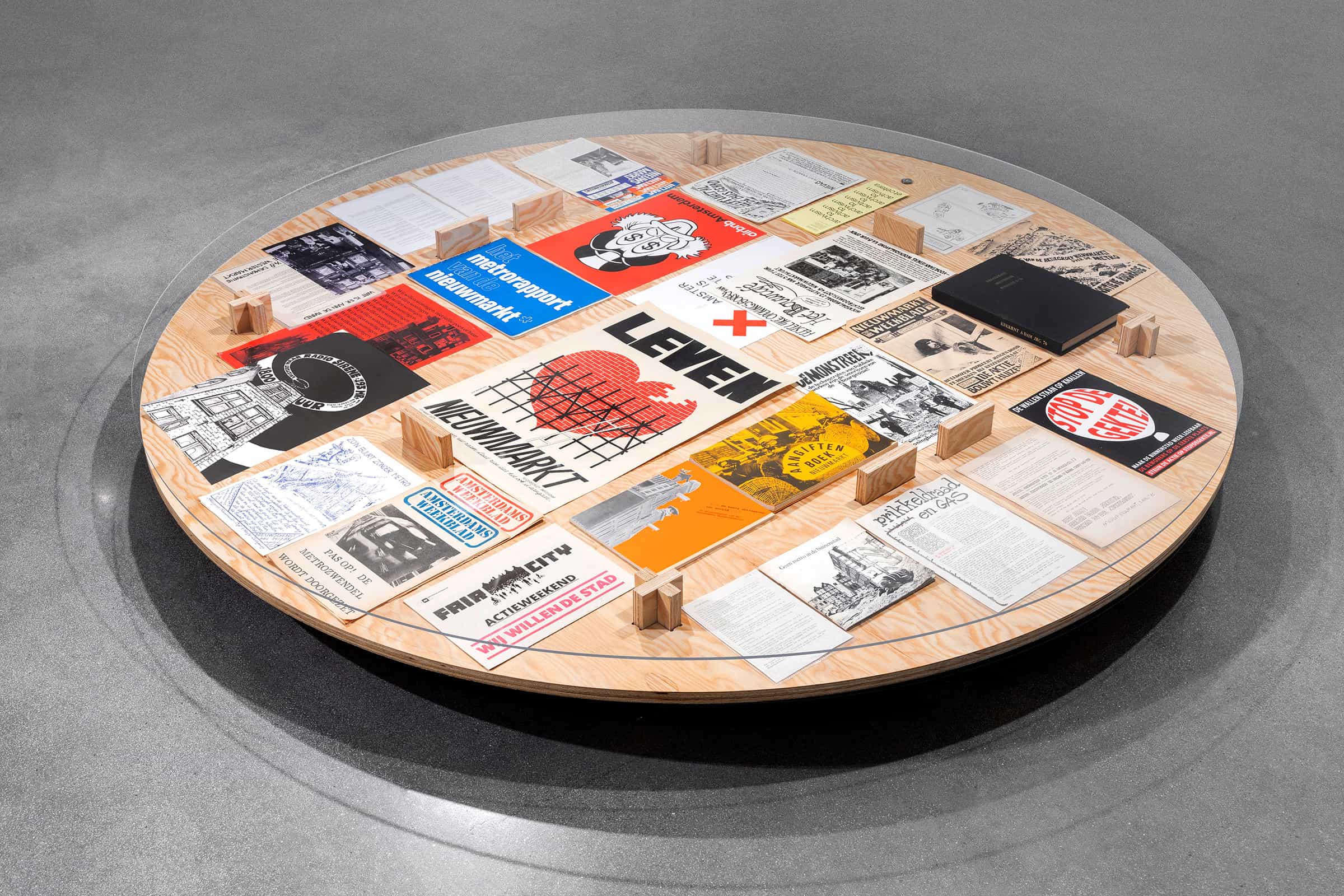

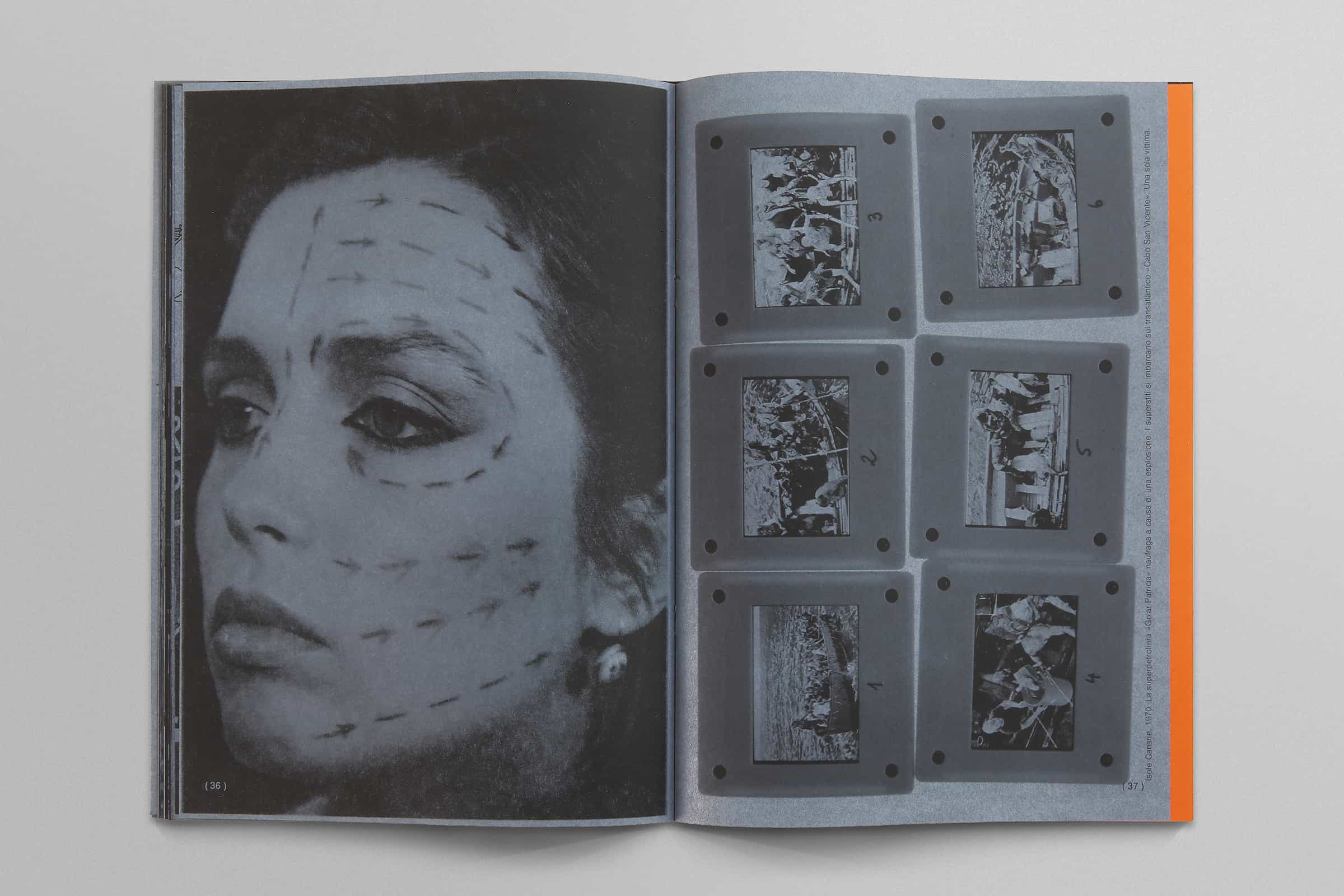

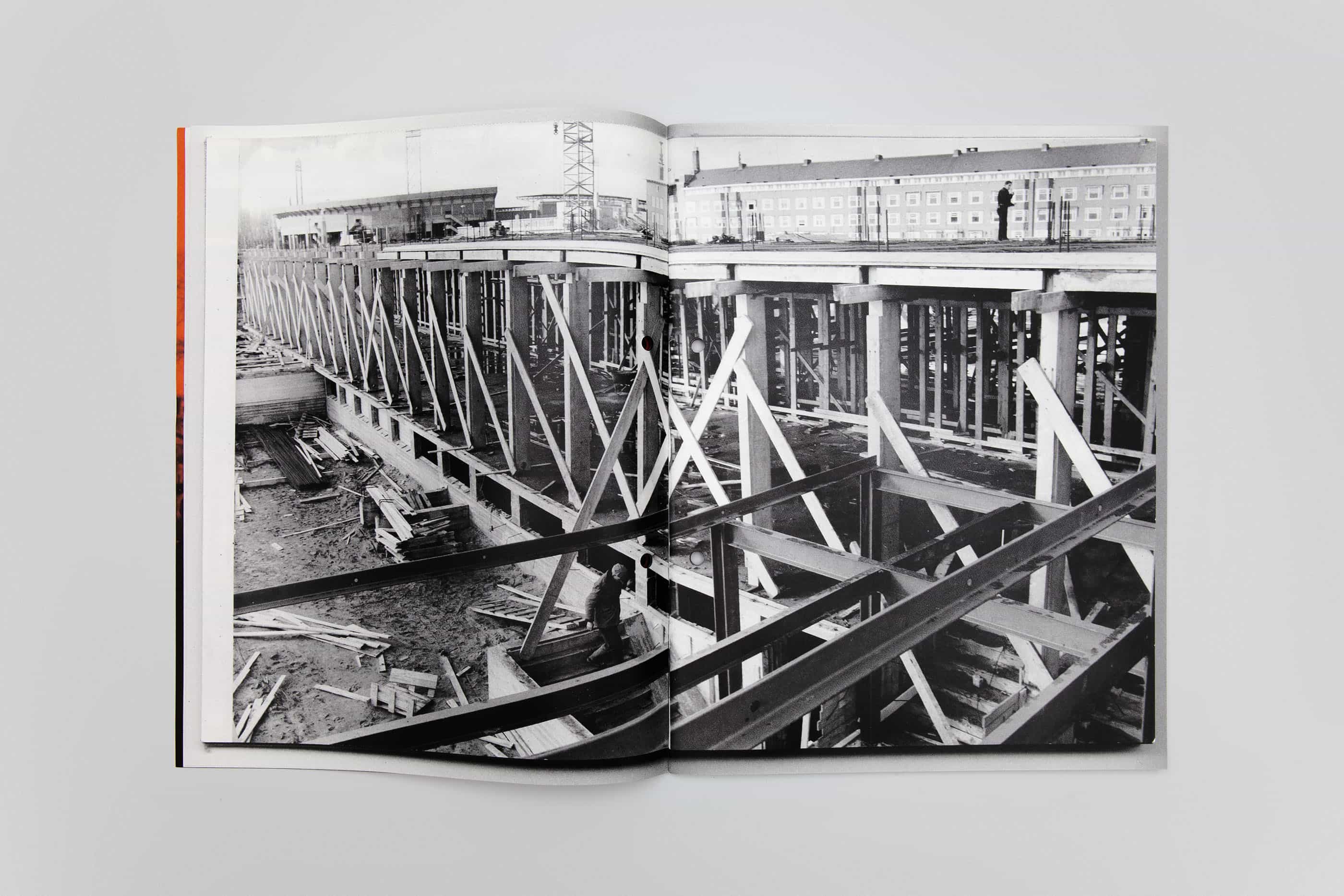

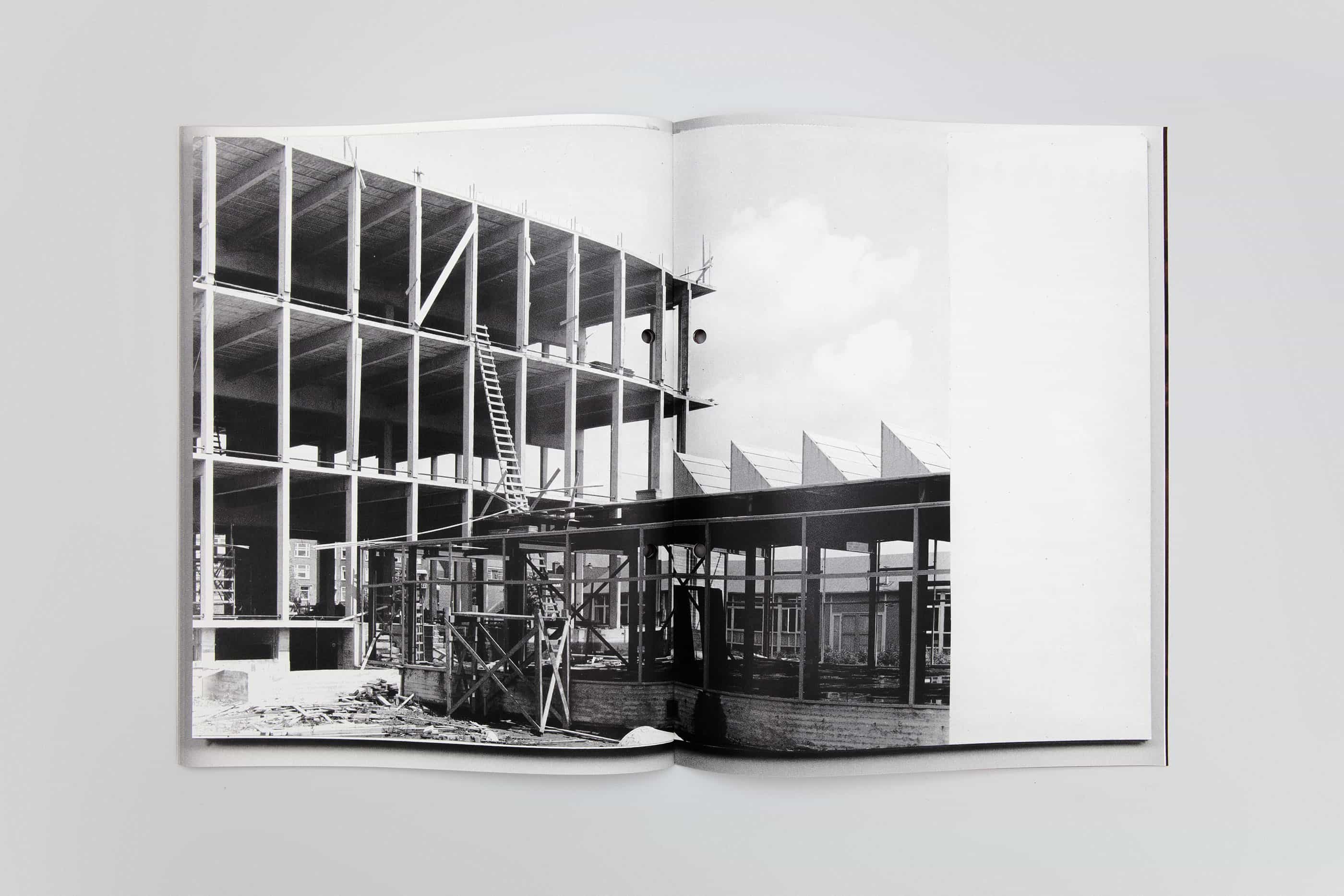

In the decade following May ’68, the notion of the artist/worker led to artists and intellectuals joining forces with students, laborers, cleaners and factory workers in order to challenge the functioning of art institutions, universities and factories through a set of collaborative practices and political actions. Pioneering exhibitions like Tucumán Arde (1968) by Grupo de Arte de Vanguardia engaged with the struggle of Argentinian workers from the Tucumán region that suffered from the disappearance of the local sugar industry. Berwick Street Film Collective in London supported the effort of the Cleaner’s Action Group to unionize severely underpaid night cleaners from different office buildings in London with the realization of the documentary film Nightcleaners (1975). Parisian filmmakers Chris Marker and Jean-Luc Godard contributed technical training and film equipment to the Centre Culturel Populaire Palente Orchamps (CCPPO) to set up the Medvedkin Group which was a film project initiated by politically engaged workers from the Rhodiacéta factory in Besançon and the Peugeot factory in Sochaux and based on the collectivist ideas of soviet filmmaker Alexander Medvedkin.(6) Simultaneously, in the Soviet Bloc, film clubs in the different countries became more permissive with cultural expressions not conforming to the official Soviet rhetoric and freeing itself from the straitjacket of social-realism.

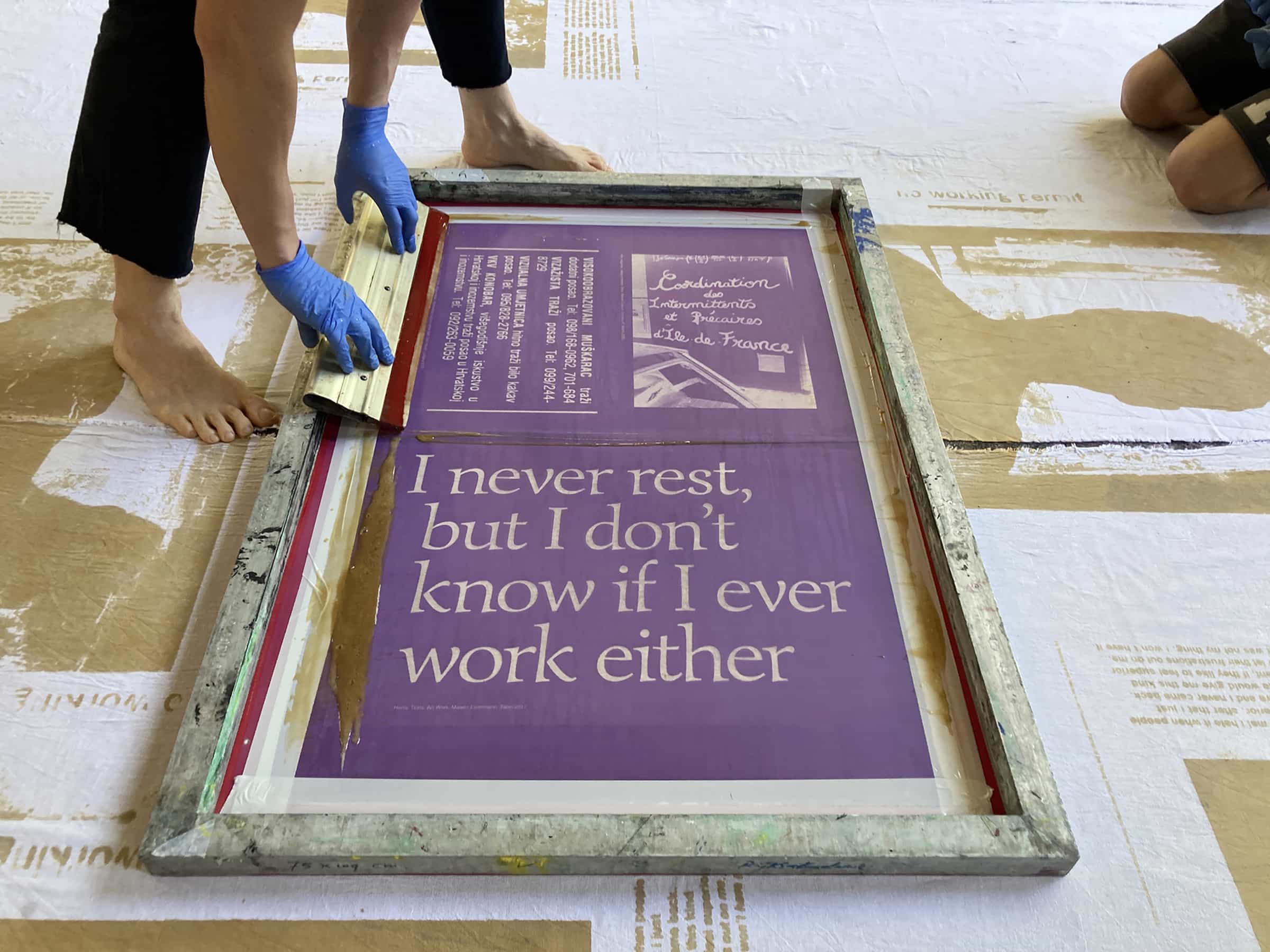

An illuminating internal letter(7) published in October 1969 analyzes the developments of the Medvedkin Group one year after its foundation, in a moment of crises when there was only three members left in the group. The letter describes the relation between the Parisian support group and the workers in Besançon and Sochaux stating that, “The Medvedkin Group is a myth to which Parisians send their support to.” The document shows the difficulty to keep up a continuity in the film activities of the worker-led group and offers some solutions; either the group dissolves and hopes for an organic reactivation by workers themselves or it becomes part of the CCPPO and welcomes intellectual workers to join in. The document ends with an exclamation of, “The Medvedkin Group has died! Long live the Medvedkin Section!” It is relevant to mention that one of the main activities of a so-called Medvedkin Section would be to create an archive of social struggle, strikes and revolutions for which they would need a skilled archivist to volunteer. This is an example of the difficulty to keep momentum in artistic collaborations between intellectual and manual workers. Are there differences in the dedication that different actors of such collaborations can keep up with? Is there a difference of interests? Are artists willing to integrate a collaborative methodology to their practice, whereas workers might not see the outcome of such a collaboration useful for their militancy? What practice has taught is that there is a physical limitation of artists and workers who usually commute between their regular remunerated jobs and little or non-remunerated activist activities, which brings us all to a state of exhaustion.(8)

Looking at histories of the artist as worker, and the worker as artist, it is of relevance to determine that geographical, cultural and educational privileges do not dissociate the artist to be a worker, or the worker to be an artist, but still there are differences that prevail. Our common interests and solidarity are crystalized through collaborative educational practices and political actions. Our skills can be shared, but how can our fragile cultural and (under)privileged social positions be unveiled and reworked together? What educational opportunities can we explore, in solidarity against oppressive hegemonies? Cultural studies have helped us to define that, “People have to have a language to speak about where they are and what other possible futures are available to them. […] These futures may not be real; if you try to concretize them immediately, you may find there is nothing there. But what is there, what is real, is the possibility of being someone else, of being in some other social space from the one in which you have already been placed.”(9)

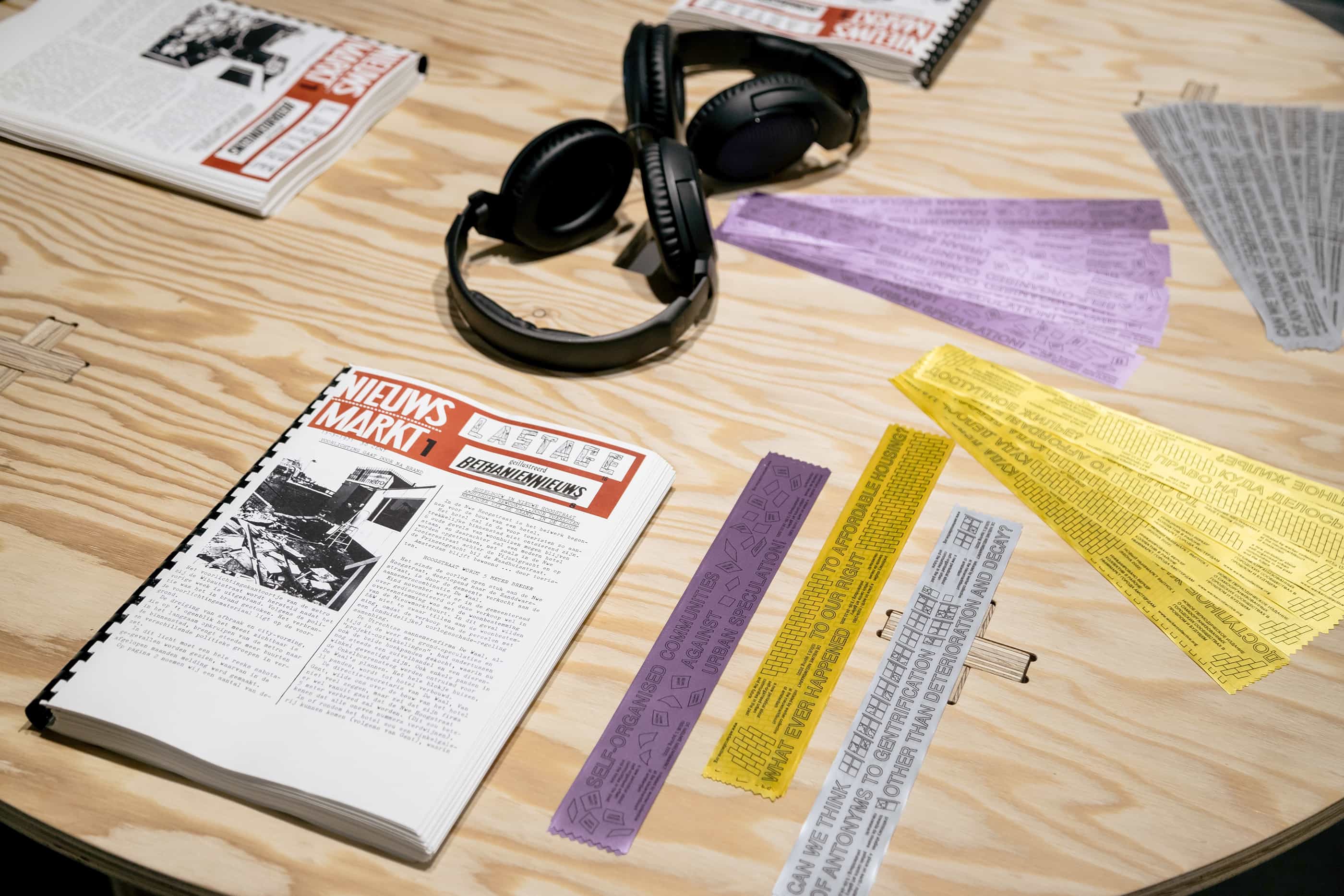

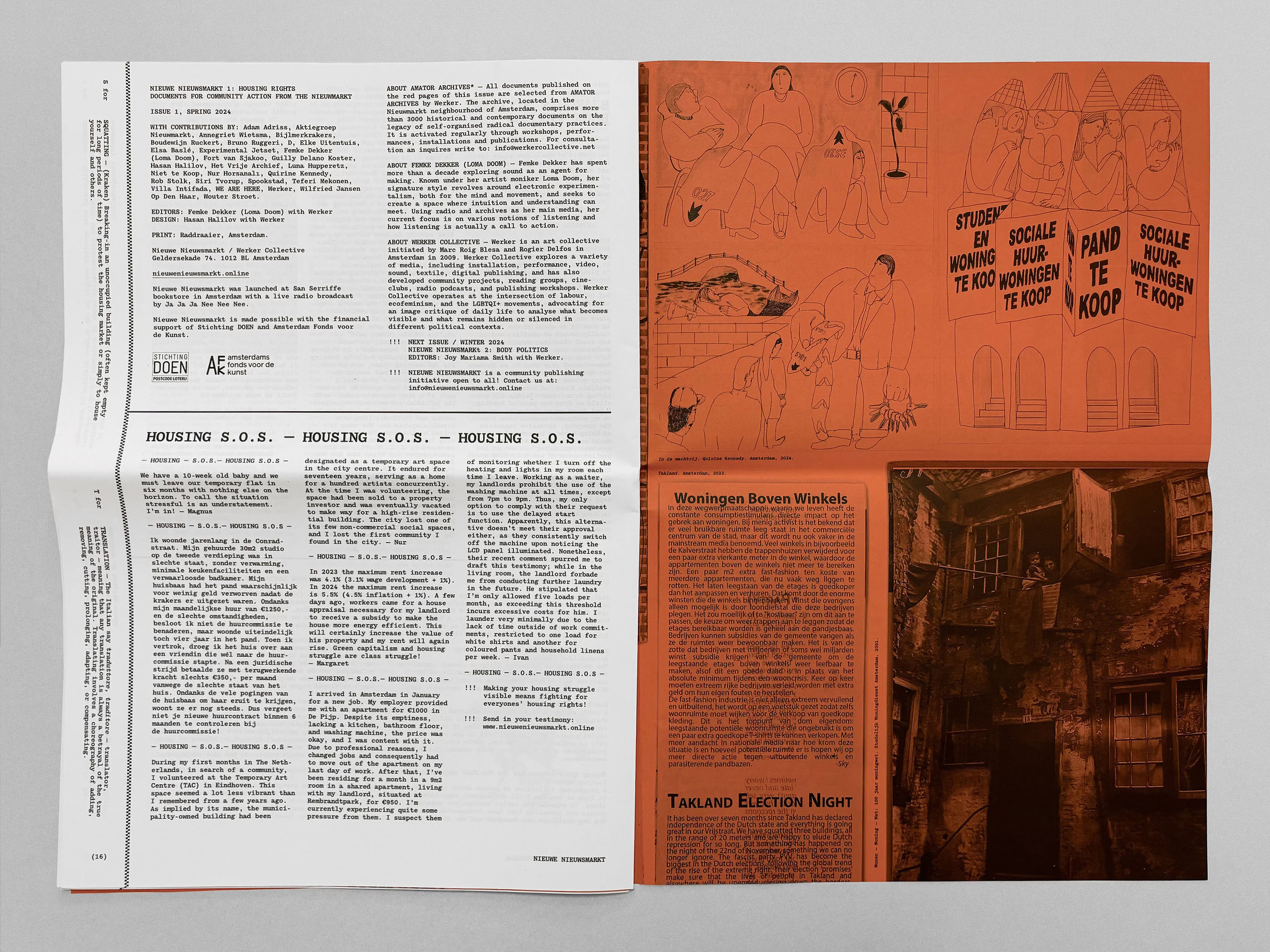

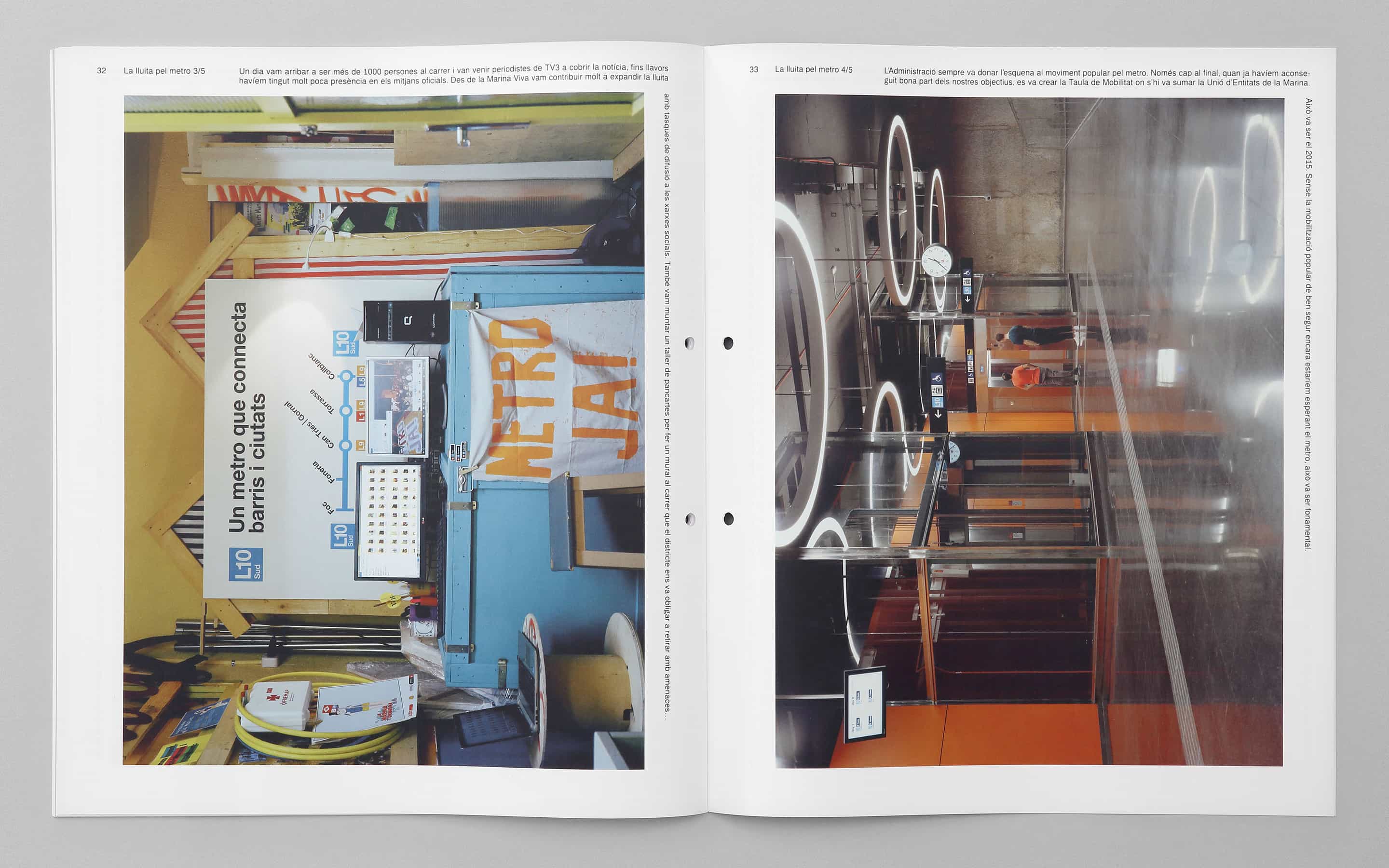

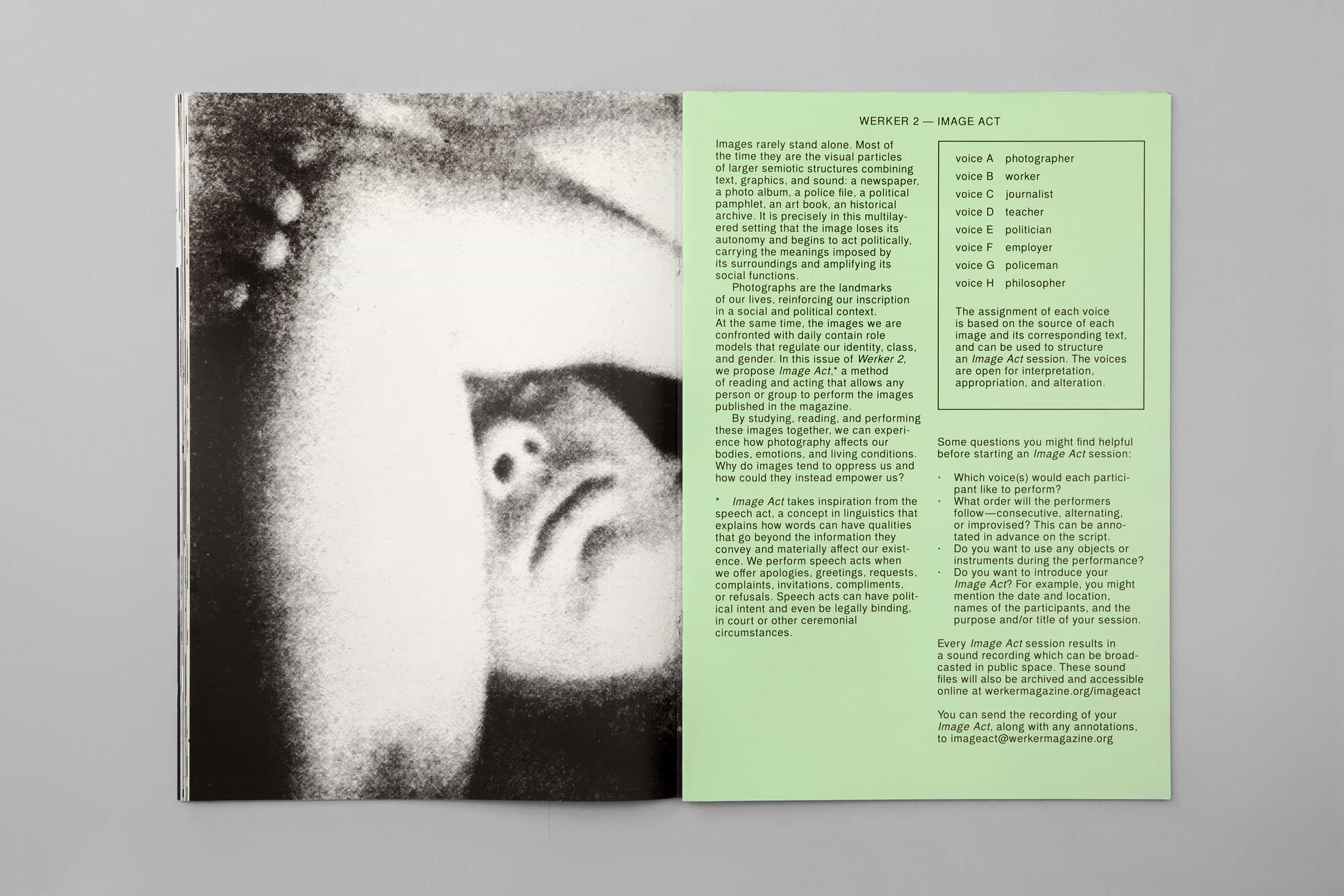

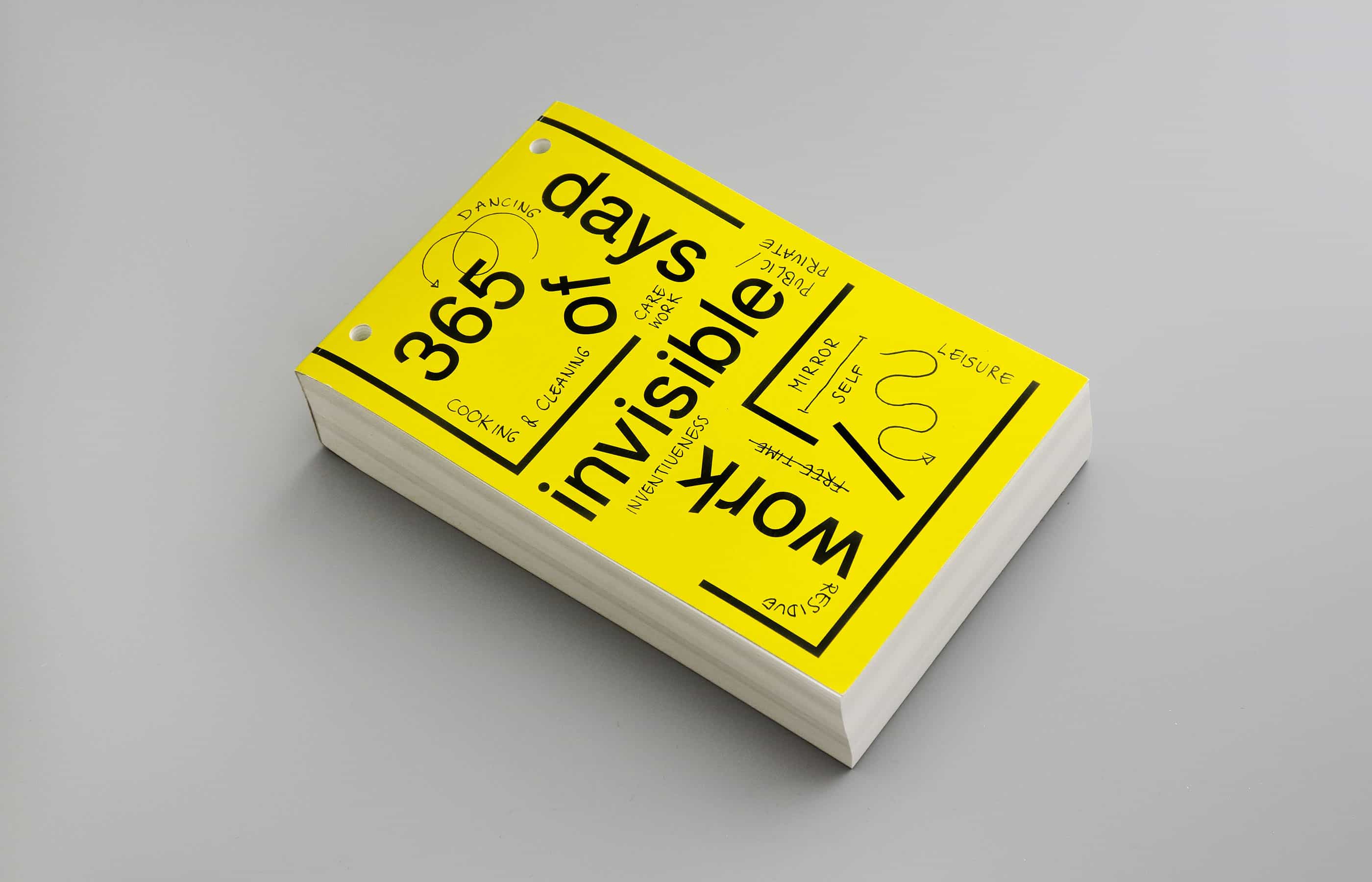

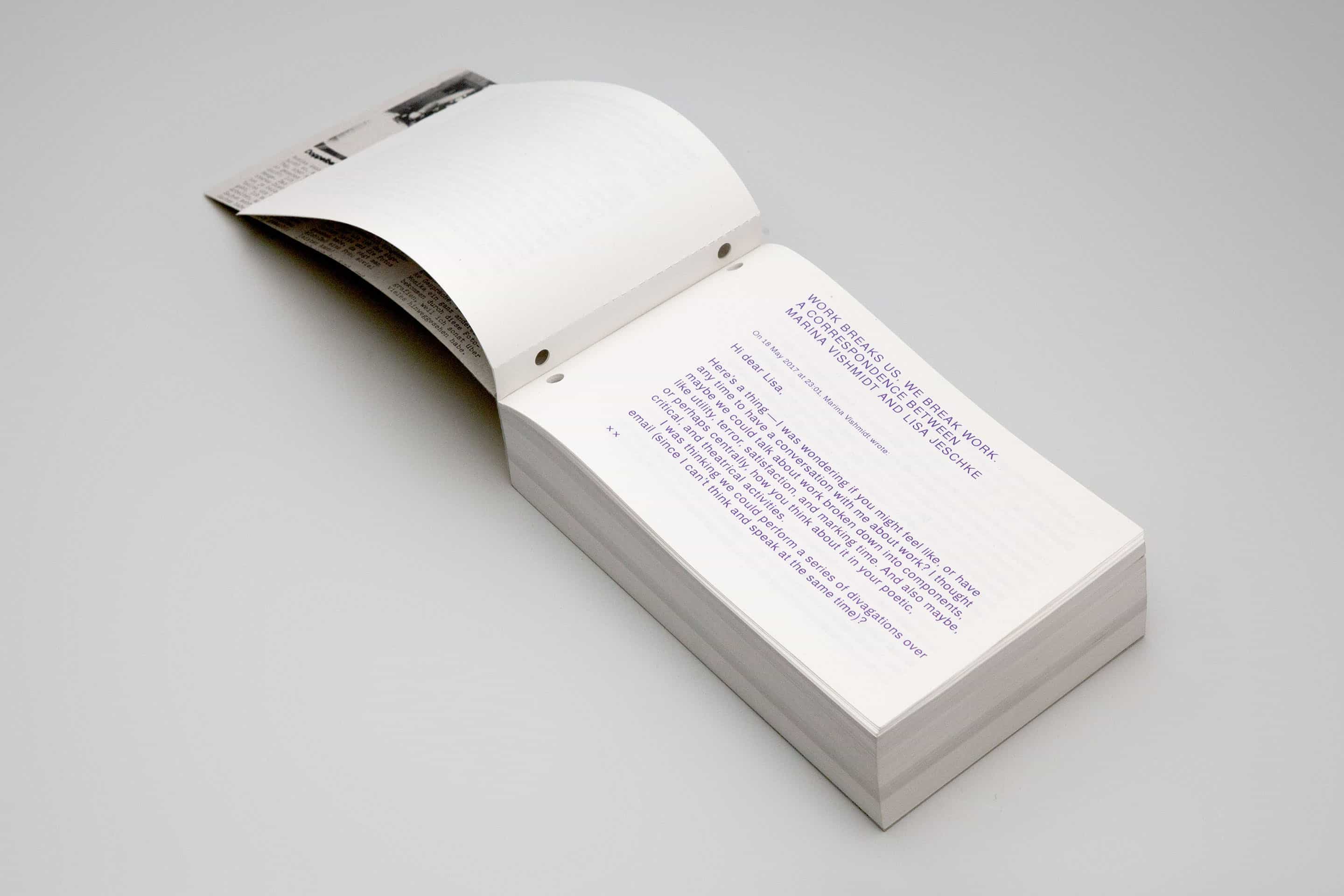

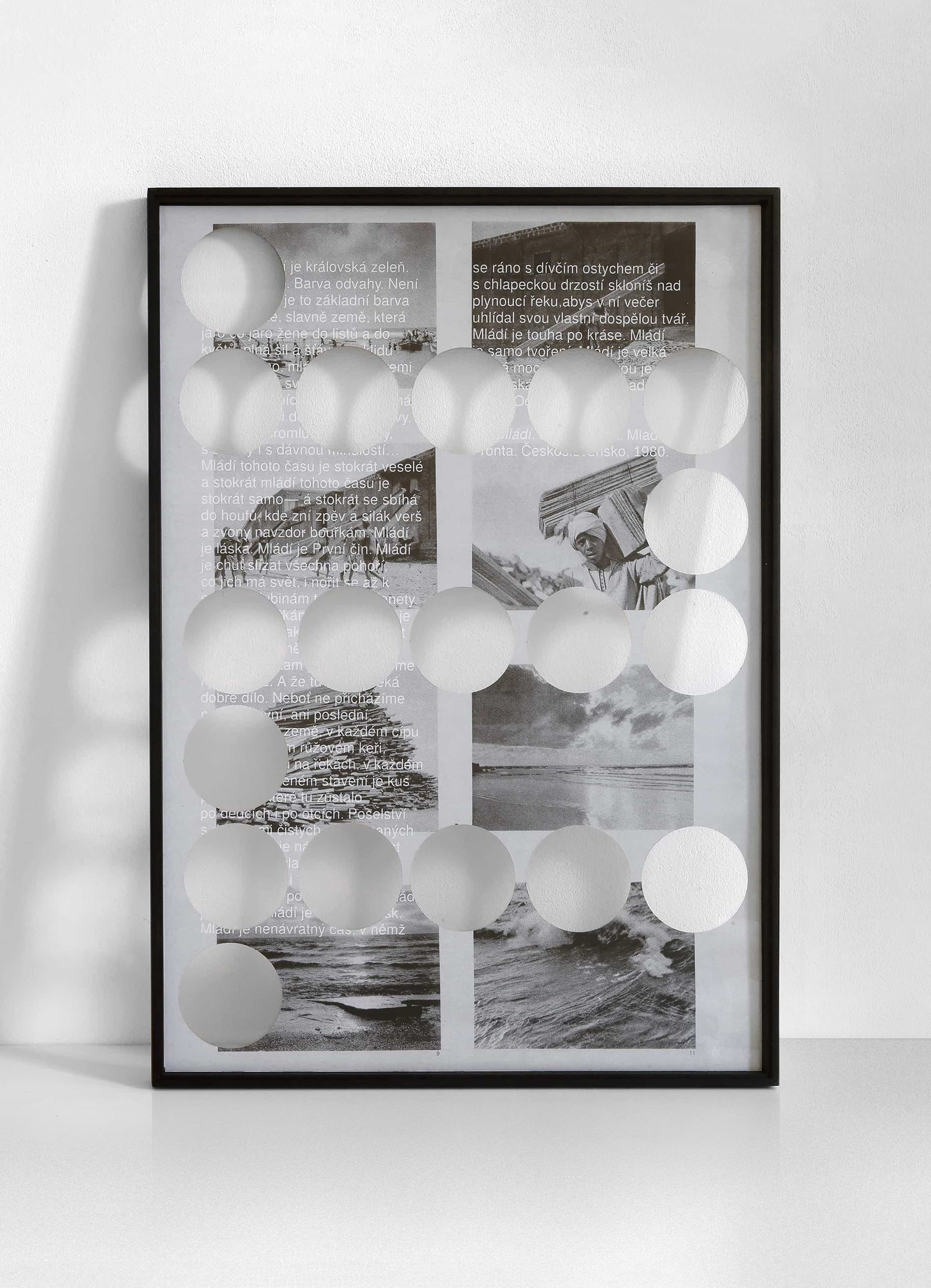

Examining the home as a social setting in which capitalist exploitation takes place, the Domestic Worker Photographer Network(10) initiated by Werker Collective in 2011 as a part of The Grand Domestic Revolution by Casco Art Institute: Working for the Commons in Utrecht, is a critical platform for workers from different fields to share their own experiences of working at home. The network functions as a technology of care’, to invigorate self-representation as a social practice in order to fight the isolation and invisibility of house workers. It calls attention to the hegemonic structures that make reproductive work invisible and aims to disrupt the visual material that propels this invisibility in dominant media. The Domestic Worker Photographer Network proposes a space for imaging workers solidarity and most importantly supports the current struggle of migrant domestic workers who campaign to demand respect, recognition and equal rights for their care work. This stands in solidarity with the ongoing campaigns of self-organized domestic workers world-wide who demand the ratification of the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Domestic Workers Convention (C189) to equivalate their labor rights to other professions in terms of working hours, access to social security, unemployment benefits, pension, paid holidays, etc.

Despite obvious differences in terms of social recognition of the work of artists and that of domestic workers, we can identify a correlation between the demands made by domestic workers and the struggle of freelance cultural workers who, in many countries, suffer from irregular income, no right to pension, high rent, unpaid internships or working extra hours. In addition, a variety of forms of systemic racism and exploitation forces these sectors to accept lower incomes compared to their level of studies. It is important to mention that many migrant domestic workers hold higher education diplomas. Workers that don’t take part in the productive economy of our societies are directly and systematically undervalued, instrumentalized or neglected. Simultaneously, this applies to education and health care workers who suffer from the effects of successive budget cuts and privatizations of their sectors. When it comes to reproductive and care work, its historical under-valorization has an impact on a representational level. Domestic and care work are invisible forms of work and this invisibility is something that concerns us as artists and others engaged in reassessing the politics of representation in our societies.

Unsolvable oppositions fed by assumptions about professional identities and (non-) privileges have the effect of canceling the possibility for solidarity and collective action. As mentioned in the above histories, social change is achieved through the sum of intellectual and manual workers uniting against forms of oppression that are always exerted by a few in detriment of a majority. Competition and difference stand opposite of solidarity and commonality. The dismembering of the social body reinforces the oppressive status quo of the dominant class. How can collective action be articulated around the myriad of differences and specificities that our vulnerabilities deserve to be cared for? How can these differences be acknowledged and become part of our common struggle for social justice?

As an assembly of bodies with a multitude of selves, we would like to be identified not just as artists, domestic workers, teachers or mothers. As much as our professions define our position in society, our identities are constructed around parameters of gender, sexuality, class, race and more. This multiplicity of positions and vulnerabilities that are in all of us — which abolishes a monolithic notion of identity divided in binaries — is where solidarities can be articulated; to construct a counterculture of non-conforming bodies that reject the capitalist, white patriarchy. Thus, to createtechnologies of care. is a collective task for artists, activists, mothers, workers and oppressed populations at large. It is necessary and urgent to relentlessly rearticulate worker solidarity against the disintegration of the social body that we are facing today, immersed in global pandemics and monitored by surveillance systems that screen our online/offline political activisms. Yes with us, never about us.

Werker, Amsterdam 2021.